Confessions Of A C-2 Greyhound Carrier Onboard Delivery Pilot

A C-2 pilot describes how the workhorse Greyhound we know today was a very finicky and neglected aircraft years ago.

BY JAMES WALLACE AND TYLER ROGOWAY NOVEMBER 29, 2017

The Navy's relatively tiny C-2 Greyhound community and the carrier onboard delivery (COD) mission was in the news last week for tragic reasons. A Greyhound flying out of Okinawa to the USS Ronald Reagan went down near the carrier, which was operating hundreds of miles from land. Amazingly eight of the 11 souls aboard survived and are in fine condition, but sadly three didn't make it including one of the aircraft's pilots. They were declared lost at sea after many hours of searching by US Navy and Japanese Navy assets.

The fact is that the C-2 has a pretty impressive safety record, although according to one pilot who flew it in the 1980s, before the type was upgraded significantly it was anything but reliable and its critical mission lacked support, as well as appreciation, from the Navy.

James Wallace came to fly the C-2 at what is now viewed as something of a golden era for Naval Aviation. It was the early 1980s and the Cold War was in full swing. The Reagan Administration was executing a new form of foreign policy and backstopping it with massive defense spending. Still, the C-2 community didn't see much, or any, of this windfall according to Wallace, at least not early on. What he did experience was a neglected flying community infested with faulty officers and an airframe that was run-down and never really well prepared for its mission in the first place. And he almost paid for the aircraft's chronic deficiencies with his life.

But the unique carrier onboard delivery mission provided Wallace with an equally unique set of skills, namely how to operate on the fly from anywhere in the world with minimal support. He ended up turning these experiences, as well as his flight skills and his geology background, into a number of successful businesses, including Avior Technologies and Greystoke Leasing and Engineering, operating a wide number of aircraft in some of the toughest and most underdeveloped neighborhoods in the world. As James puts it:

"I really attribute my success and ability to work in war zones to the resourcefulness I learned flying the POS COD and its goofy mission. It made it so I am completely unfazed when things go wrong, terribly wrong, in an aircraft. I now have five complete engine failures, glide to landings in my career."

James Wallace's recollections remind us that the remodeled C-2s that are in need of replacement today are the product of some very tough lessons learned by those who flew their finicky and underpowered predecessors. It also underlines how critical the C-2's mission still is, regardless of the amount of attention it gets. This is especially important considering the Navy controversial plan to replace the Greyhound with V-22 Ospreys.

Here's James's story.

USN

Hitting the Greyhound trackFlying in the Navy is truly a real adventure. Well it was for those of us that entered the service as refugees from the final days of the “draft lottery.” I ended up in NROTC at UCLA in the early ’70s and it was a joy. Everybody hated and shunned us.

Well we finished up our degrees and most of us at UCLA got shunted off to the flight program. Being in those “tweener“ years before Regan took over, we got sent to Corpus Christi in the late ’70s to a flight program that was barely working. There we flew the last gasping T-28’s for our initial and intermediate flight training. We were supposed to transition to US-2B’s (the “Used To Be”) for our advanced flight training and carrier qualifications. The US-2B’s ended up being condemned just as we were being moved to the squadron. So in a fit of desperation the Navy got the T-44 for us to do advanced maritime multi-engine training. But there was one tiny problem—you can’t land a T-44 on the carrier.

We only had two prop aircraft that routinely landed on the carrier at the time, the C-2 Greyhound and E-2 Hawkeye. Both were absurdly expensive to operate and unsuitable for initial training of “nuggets” in the carrier environment. So they dusted off some T-28C models from the boneyard at Davis Monthan AFB and gave them a fresh coat of paint.

We qualified on the carrier in them and were last people to ever do single engine radials on a U.S. carrier. It was fairly useless training for us, as the radial single engine approach to landing on the carrier is a cut pass versus fly onto the deck pass. And we didn’t do catapult shots, we did deck runs for take off. However, it did carrier qualify us, but they would “enlighten” us later on at the RAG (replacement air group) on the proper way to do it.

I received my orders out of Corpus Christi to VR-24 to fly the Super COD out of Sigonella, Sicily via the RAG RVAW-120, who flew E-2s. Well, if I ever had any ambitions to have a career in the Navy, it ended there. There was no “career path” for a Carrier Onboard Delivery pilot.

This was immediately apparent when we got to the RAG, and were greeted with “oh, another COD puke.” We did our training in E-2C models, since the TE-2As were permanently un-serviceable, at least for the 11 months I was at the RAG.

Trust in CODThe E-2 is an unusual aircraft to fly, aside from its unusual looks. It was unstable in two axes. That made it a handful to fly and a joy to land on the carrier. Little did we know, the C-2 was unstable in all axes. So much so that the prototype killed the two Grumman test pilots during spin testing. This led to a big warning in the NATOPS manual: "Do not enter a spin.” As if I was going to try it out for fun one day with a load of cargo.

The C-2 and E-2 shared a common engine platform, the Allison T56. A fine engine—lots of power instantly available. It ran at a constant speed with a variation of -6 to +3.5 RPM. The core runs a gearbox via a shaft. Which in turn runs a propeller that is actually regulating the engine speed via a whole host of systems. First off the propeller is a separate hydraulically actuated and electronically controlled unit. This is protected by an auto feather system, a negative torque system, a pitch lock system, and finally a decoupling device to separate the engine from the gearbox.

Oh, this was a fun system to maintain, especially in the carrier environment. First off, the auto feather system would occasionally detect a power differential between the two engines via the Negative Torque System during a cat shot, leading to one of the engines feathering as you went down the cat track. You were usually at max gross weight when this happened making for a fun scramble to keep the aircraft flying and setting up for an air start when things settled down.

The engine, if for whatever reason it chose, due to a low RPM situation, would automatically shut down at 94% since the bleed valves would open and it would stop generating power.

The last fun failure was a pitch lock. This system was to keep the prop from over-speeding and would lock the props pitch setting at the last point it was operating at. This was our worst nightmare. If it happened at altitude, we would have what was in essence four giant speed brakes spinning on the wing, which would only get worse as we descended.

This happened to one of our C-2’s at Barcelona, Spain. The aircraft was virtually un-controllable on landing, unless there was arresting gear on the field. Barcelona didn’t have it and this led to a rather famous quote from the pilot: “I knew we were in trouble when the main landing gear passed us by.” It had ripped off the nacelle after going off the runway over a ditch. Un-believably, they re-worked that aircraft and gave it back to us, 18 months later.

The C-2, aside from being a paper napkin design born at a bar in Bethpage, New York was a very limited production aircraft. So much so that of the four we had one was the second prototype, still serving in the ’80s.

It was 1,000lbs heavier and mostly in the aft section. It even had its own set of maintenance manuals. It flew very differently than the other three, making it challenging if you had not flown it for a while or were taking it on the boat.

The C-2’s mission was very diverse and very critical to the Navy, which wasn’t reflected in how we were supported. The priority for logistical support is a hierarchy much like this: Pointy number one is fighters, then attack, then anti-submarine warfare (ASW), then electronic warfare (EW), then space aliens and pond slime and finally, oh yeah, the C-2 guys.

We had the same engine family as the E-2 but we had 650 less horsepower per side and operated 4,000lbs heavier. So we had a non-standard bastard stepchild engine that gave us no end of problems, and they were old, real old.

The aircraft had an auxiliary power unit (APU). Nice since the engines needed air for start. Well that APU only supplied air—no power, no hydraulics, just air. To make it worse, there wasn’t any associated plumbing. The crew had to plug a hose into the fuselage receptacle and run it to each engine in turn and plug the hose into the engine’s nacelle. Then un-plug it all roll it up and put it back in the airplane! What were they thinking!?

We always carried four cartons of Marlboros in our secret compartment to help us obtain an air start cart at remote airports. The lousy APU was anything but reliable.

Unglamorous but essentialThe Navy needs the C-2 to actually fight a war. We had two critical missions—supply engines for the carrier’s air wing as replacements and carry nukes back to the boat when they wanted to have nukes on them.

During war fighting, aircraft eat engines with foreign object debris (FOD) being the biggest problem. Apparently flying through the debris cloud caused by your attack on a ground target, or the randomly disintegrating aircraft you're fighting against, doesn’t do much good for a jet engine. We would be tasked to deliver two to four engines a day during combat to keep the air wing operational.

Then there was the other mission critical parts, the general stuff, from landing gear to rotor blades. We also had the capability to carry liquid oxygen (LOX) at 300 gallons a shot. This was a comical mission for us. We loaded on this huge skid mounted tank of LOX and we then connected its vent to on overboard vent. We had to wear parachutes when we flew with it onboard. Why? Who knows. If it failed in flight I suspect our first warning would have been the large explosion hurling aircraft bits and pieces of us in different directions.

We also carried personnel in 24 aft facing seats—four abreast facing aft with two tiny windows for one row to look out of. These poor souls would get to experience either a cat shot in a dark tube or a fun ride down to an arrested landing, in the dark. Frequently, you would look at the passengers (pax) shambling out white faced as they unloaded (we called pax, “self loading cargo”).

Our final and least critical mission, at least to the Navy, was carrying the mail. This was the most important to the ship’s crew and general morale. It was also fun for us as it made us modestly popular. Most of us sported USPS Letter Carrier patches on our flight suits. One of our aircraft even had a big sticker from a postal truck on the nose wheel door.

The postal mission seemed to be so important to the ship’s captain that we could use it as leverage. We were usually detached moving around at will for 30 days at a time. We would operate from someplace convenient, hit the ship and go to someplace else to spend the night. They didn’t like us to stay onboard the ship as we were too big and took up too much deck space. We took the break after the F-4s and F-14s landed so we could load and parked right behind the jet blast deflector on cat 1. We launched right after the fighters. It was rare we would spend a night onboard unless the weather was bad or we had mechanical issues. So normally we would get to shore and bed the aircraft down at night and go off to search out some seedy hotel that would be covered by our meager per diem rate.

On the road chasing carriersFrequently we wouldn’t get to bed until 10:00pm. We didn’t have time for dinner, we had to launch at sunup to make our overhead time above the carrier, which was frequently 300 to 400 miles offshore. So we rarely got meals and depended on our box lunches supplied by the carrier.

Well for whatever reason the air transfer officer (ATO) on the USS Independence thought this was some kind of joke (we hit virtually every carrier in the fleet, so rarely had any special relationship with one) and we got garbage in our box lunches. So after a few of these, “lunches” I took it up with the Air Boss. I explained that this was frequently our only meal of the day and my crew and I are living like gypsies with no support. So when I get back to, in this case Alexandria, Egypt, I am going to do a good walk around on the aircraft (I was the Airframes Division Officer). I will most likely write up around 80 gripes on this antique, whistling shitcan. So we will sit in Alexandria until somebody at the Smithsonian rounds up the parts and ships them to us so we can get back in the air. Then, maybe in a month or two, you will get your mail again!

We got much better meals after that, in fact, superb meals.

The C-2 had a large suite of comm gear, including a UHF—standard fare for carrier aircraft—a VHF Civilian com radio, and an HF with a 200 foot trailing wire. We would typically get our next day’s tasking via the HF from Air Services Coordination Mediterranean (ASCOMED) in Naples. We would vaguely know where the ship would be in 24 hours. They would give us a PIM—projected intended movement—the day before or occasionally we would get it from the local base or embassy in hard copy form. It was classified, so it was not transmitted via radio.

Well the damn boat never went where they told us it would be. This was unnerving since we could not refuel in flight and only had so much range. We frequently went out to the ship without the possibility of return to shore unless we refueled on the boat. Well we would navigate out to the boat with an OMEGA system, a now defunct long-range navigation system. This would get us to the general vicinity of the boat. We would then use our advanced Bendix black & white weather radar in map mode to find what looked like the battle group—a bunch of blips clustered around a big blip. Sometimes, the E-2 would be kind to us and give us vectors, but the carrier frequently operated in ENCOM—no radio communications.

It was a wonder we found them as frequently as we did. There were times I couldn’t locate the ship and I would transmit in the blind that we where turning back “with 4,000lbs of mail” and magically the E-2 or marshal controller onboard the carrier would answer us and give us vectors.

USNThe arrival of the COD means mail call for many sailors.

Our comm gear was one of the frequent failures. In Grumman’s infinite wisdom, they placed the VHF radios in the prop arc in a rack behind the cockpit. These were the same models used in the P-3 Orion. We really needed this radio, as we had to return to some civilian field someplace from Mombassa to Reykjavik. They tended to fail after the cat shot. So once, in my primate curiosity, I had the plane captain remove the box and bring it up to me in the cockpit. I was not going to try to get back to Athens NORDO (no radio).

I took out my swiss army knife and opened the box and found all the transistors rattling around in the box. Cleverly these were all socket-mounted and would eventually rattle loose. At least they all seemed to be the same part number and I plugged them back in. Magically this worked and became a standard post-cat shot procedure.

We did a lot of VIP flights. The Navy likes to do “dog and pony” shows for various bigwigs around the world. Normally, we had special seats for those flights. Special, being they where actually clean, not the normal hydraulic oil soaked ripped up POS’s we normally used.

You see we would go from all passengers to all cargo between lifts and have to un-track all the seats, stack them up and strap them down, build up the cargo cage and set up for cargo. This didn’t do much for the condition of the seats. I have personally taken folks such as ministers of defense of UK to President Mubarak of Egypt to the boat, along with all their entourage. We hated VIP lifts. They were a huge opportunity to screw up something and provided little praise or benefit to us.

One Air Force four star general took offense to my being so young, I was 23.5 years old and the plane commander. He wanted the much more seasoned older Lieutenant Commander, my co-pilot, to fly him out. I patiently explained that as a flag officer he can take command of the aircraft and do as he wishes. However the Lieutenant Commander here is not qualified to land this aircraft on the boat and I am feeling suddenly un-well and will stay ashore. My skipper commanded me to grow a beard to appear older.

Note the eagle lifting the engine can. This was the C-2's most important mission.

The "Elephant Graveyard"Our squadron, VR-24, was uniquely staffed and frequently referred to as the “Elephant Graveyard.” We had more commanders and lieutenant commanders than lieutenants. This was due to the following situation: If you screwed up someplace in the Navy but not enough to be kicked out, they sent you to us to get your 20 years in.

We also had some contract re-enters to fill up the roster as well. The problem was we could never get a boat deck to do their quals (carrier qualifications). So we only had four plane commanders to staff up 4 aircraft. Not too bad since we could only ever keep three of the aircraft even remotely airworthy at a time.

VR-24 also was unique in that it was a composite squadron. In addition to the C-2 we had a couple of C-1s (cargo variant of the S-2 Tracker), which were the last in the service and rarely went to the boat since there was no avgas on the boat. We also had T-39s (VIP Sabreliners jets), H-53Ds helicopters, and C-130s. So our squadron was actually several tiny squadrons in one.

The upside down distribution of senior officers led to a situation in that they had no ground job, and were referred to as “team pilots.” In other words they were there simply for flying and had no division or department head jobs. We never took them seriously and they tended not to give us any trouble, they were there to retire. It just made it awkward on detachment since the senior plane commander commanded the detachment.

We tended to have our usual crew which quickly became like family, just being the four of us for a month or two. Of course once one of the “elephants” had just joined the squadron, they didn’t get the relationship and would become offended when my crew would refer to me as “boss.” “He is a lieutenant in the US Navy” one of the new elephants shouted at my crewman, “you will call him SIR!” “OK, Boss Sir, what’s the plan for today?” I did mention we had no illusions as to our future careers in the Navy.

Resorting to the "alternative supply system"Our supply problems were so bad that our flight equipment was typically in tatters. Our squadron never had spare flight suits, gloves, sunglasses, boots and so on. We would have to use the “alternative supply system” to get our gear. This would include snatching up stacks of “Star and Strips” and taking them down to some supply chief on the boat and trading them for what we needed.

Frankly, we got quite a trading empire going to keep ourselves supplied. We would get whatever trade goods we could on shore—rugs, trinkets and such—to trade for gear—not booze, dear god we would go to prison for that. We would occasionally spirit one of our buds off the boat to spend the night onshore. This could have led to huge disciplinary issues if we had ever gotten caught.

We were discrete. We were on the bottom of the carrier pecking order, which runs downhill from fighters. One of my buds from flight school who was flying pointy planes, once talked to me on the boat on one of our rare overnight stays. He asked if it wasn’t humiliating to be stuck in such a POS aircraft. I replied “yes it isn’t the most glamorous thing to fly, but I’m going back to shore today to have a beer and talk it over with some chick in the bar back in Scotland.” Not living on the boat was refreshing.

I only had to do one four month deployment FLOATEX in the Indian Ocean. It was more or less a waste of time, since almost everyplace we could go was out of range. Once a week, the ship would steam over closer to Oman and we would fly over to Masirah, a small chunk of the moon that was offshore of Oman—not a single plant on that island. We would meet up with a C-141 and swap out whatever cargo and passengers we had.

Mostly we bored holes in the sky. They launched us everyday to get us off the deck. We would fly around randomly picking up ships on our weather radar and photographing them for the intel boys. We also took a load of folk off the carrier so they could get the experience of a flying off the boat. We would let them cycle through the co-pilot seat to get a decent view. This was a big reward for the hard working enlisted guys on the boat.

Saved by CyprusI had a large number of emergencies in the C-2, way more than any other aircraft I ever flew (76 different aircraft and helicopters by now). The aircraft were simply worn out, much like the fleet today.

My most memorable and one I am very thankful to be alive from occurred off Beirut. It was my first flight as a plane commander. At the 90 on final to land on the boat, I got a fire warning light on the left engine. I really didn’t have time to do anything but just land, the boat’s firefighting detail could deal with it. I trapped, made a call “COD’s on fire” and caged everything and we evacuated.

It turned out that a bleed air line had failed and the fire indicator was caused by hot air on the sensor. I was flying serial number 148148, the one unique C-2, it was the prototype and at that point 25 years old with nearly 50,000 hours on it. It was in a category beyond POS and started its life as an E-2. It was hacked and built into a C-2.

I launched off the next morning, deadhead—no pax or cargo—since it was a transfer back to base to complete the rest of the checks after the emergency. The cat shot was the normal thrill ride and we were climbing really fast as we were very light.

At around 15,000 feet I started to get an RPM TIT fluctuation on the left engine. I just happened to have the Allison tech representative on board, since he was going to check out the engines when we got back to shore. I said to myself, “oh fantastic, finally this engine is going to do it for him! Now perhaps he can finally see it and figure it out, once and for all.”

He come up forward and studied the engine and we do some tests with the prop control by switching to mechanical and to the fuel control out of electronic trim. Then the rep says “now I know what it is, you better shut it down, it's only going to get worse.” So we start to go through the precautionary engine shutdown procedure. A long list of switching things deliberately into the proper emergency configuration. Well we were down to the final item, fuel condition lever to shutdown-feather when the right engine fire warning started up.

There were flashing lights all over the board and the fire bell going off, just not on the left engine! Don’t second guess the system. I pushed the power back up on the left engine and reached over and pulled the right ’T’ handle. As soon as I pulled it the engine exploded and the aircraft rolled 60 degrees to the right—not what I expected. I must have pushed the extinguisher button 20 times but we still had very healthy flames coming out of the panels on the right engine nacelle, showing no indication the extinguisher did anything.

Well there is only so much you can do in the cockpit when things go to shit. I made my Mayday call on the radio with our position. The E-2 was vectoring folks to our position and kept us in sight. I did the last thing I could do when you're burning, I pushed the nose over and ran it up to redline—350kts—in an attempt to blow the fire out by providing more oxygen than the fire could burn. It doesn’t work by the way.

The air boss on the carrier was telling us to bail out, which if we had parachutes onboard that day we gladly would have. We normally didn’t carry them, passengers get so upset when you jump out and leave them behind. The C-2 had a beautiful bailout system. You pulled a handle and a section of the floor fell away, leaving a large hole to jump through—if you had a chute.

We were all terrified, as any sane person would be. The air boss told us to ditch, since we could not land on the boat—the deck was fouled and it would take too long to clear it for our return (we were the only launch of the day). I told the boss “not an option, we all die.” So I told the crew as we were passing 5,000 feet “I can try to make Cyprus, we may not make it, but we aren’t going to make it ditching, you know that.”

SAN DIEGO AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM148148 before its transformation from E-2 Hawkeye to C-2 Greyhound.

We headed to Akrotiri, 126 miles away—the longest 126 miles of my life. We were loosing power on the other engine the entire way and descending. We ended up in ground effect on the final approach to the runway. My hat is forever off to the fire crew at RAF Akrotiri, it was their day off and they manned up by the time we got there.

We did a landing—well kind of a landing—as I no longer had steering, just 12 applications of the brakes. We had no flaps and no arresting gear. I had to blow the landing gear down with the emergency air bottle as we were on emergency hydraulics. If I didn’t land there was no going around and I couldn’t get the gear back up anyways.

I was fast and more or less in limited control of the situation. Ultimately, to stay on the runway I blew both main tires braking differentially. By the time we stopped there was nothing left of the right main and the other main was a burning rim. We all jumped out of the aircraft’s various hatches and ran from the burning hulk with the fire crew spraying us and the aircraft.

I was running one way and one of the fire crew was running to the aircraft in a sliver suit. He had a giant asbestos blanket to wrap the burning main wheel and brake. They will blow up and red hot beryllium shrapnel shards will damage the fuel tank, which would make things so much worse. That firefighter had the biggest balls or the smallest brain of anybody I had seen to date.

After it all settled down I was really shaking and strangely really, really needed to take a leak. So I told the officer in charge there on the runway that I really needed to pee and I think my crew needs a drink. “No problem lads, we have a bar right here on the flight line, if you don’t mind warm beer!”

We ended up there for a month. It seemed we stumbled or bumbled into a secret squirrel operation the black hat guys had going on with a U-2 and its flights over the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. We seemed to have stirred up the press’s interest by going over the beach at 25 feet with apparently a bit of flame coming out of the engine. We were so sorry for ruining their day and honestly would have gone someplace else, had we known. Actually, they threw us a party a couple days later and gave us their T shirts that said, “IF WE’RE NOT HERE, WHERE THE HELL ARE WE?” Even the spooks have a sense of humor.

Since we where stuck there, we naturally had lots of time on our hands awaiting engines and gear and a bunch of parts. They couldn’t just drop the stuff off. We had to send messages up to the Brits, who would walk it over to CINAVEUR who would send it to the squadron. Then the stuff had to ship to England so they could transport it on a RAF aircraft to Akrotiri. It took forever. Well there was a junkyard of all the UN vehicles from Palestine—mine casualties and such. I drove a Land Rover Series III in Sicily. Well Land Rovers always need parts, so I scavenged a bunch of bits and pieces, including a gear shift lever.

When we finally got back to Italy, my wife came to pick me up in the Land Rover. Well the gear shifter broke off while she was pulling into the parking lot. Some of the other pilots pushed her into the space and she came out to meet me on the flight line. She was not super happy about this and she greets me with the gear shifter in her hand. I reach in my parachute bag and pull out a new one."See not a problem." Which she replied “you knew it was going to break!”

We actually fixed up 148148 well enough to fly it back to Sigonella in Italy after a month where it was completely repaired and soldiered on for a few more years until the next generation C-2s took over. I hope it is gracing a pole in front of some airport someplace. I still have a model of it on my shelf in my office.

The NARF crew at NAS North Island while James was a test pilot there.

Reflecting back and looking towards the futureWhen I got back, my skipper was proud of me, not dying and all. He told me he knew a lot of “really good pilots, but very few lucky pilots.” He said “you my boy are the luckiest one I know.” He ultimately got me my orders as the program manager and test pilot for the E-2 and C-2 at the Naval Air Rework Facility (NARF). He knew I had no intention of staying in the Navy and he told me that going in the Aviation Engineering Duty Officer route was a career dead end, but was the best possible job if you got out. It was, I ended up transferring my commission to NOAA and doing research flying for a few years.

The NARF trained me to fly a whole host of aircraft and helicopters and under some pretty intense circumstances. Most fleet guys almost never get to do a field arrestment. I did one almost once, and even sometimes twice a week. I had one string of flights that I did one every day. The NARF at NAS Alameda did the prop controls for the P-3, E-2, C130 and such. There were four guys in the shop, the oldest one retired and I received a string of seven bad prop controls, with one aircraft getting two. I did a precautionary shutdown on one engine and was on approach for an arrestment. At about 50 feet the remaining engine flamed out when the RPM dropped below 94 percent. I hit hard, real hard, but luckily caught the wire. I blew both tires and fragged the mains. Fouled the runway for about eight hours that day while they hunted around for the special rigging to pick the airplane up with a crane. The crash crew loved me.

In between NARF and NOAA I worked at Electrospace doing kind of the same thing I did at the NARF, but I was Special Mission Systems Program Manager, which paid a whole lot better. We built one-offs for various agencies and did the weird electronic warfare (EW) aircraft like refitting the A-3’s for jamming, special EW DC8s, Citations, Cheyennes and foreign aircraft like Super Mystères for South American customers. I took the job with NOAA—they sought me out—as they wanted a geologist and I was a safety school graduate who could fly anything they had. In the year before I got there they had 12 accidents with 18 pilots on staff! Well NOAA stands for No Organization At All. After 3 years, I left and started my own thing and never looked back.

I became an owner operator of a host of aircraft and repair stations in some various unique places. I still look back to my COD puke days as the most fun a 20 year old could have, with a few moments of terror thrown in.

The aircraft were horrible but the flying off of the boat and being left to our own devices all over the world was a hoot. We learned how to get into any country and deal with whatever we needed to on the ground without any support from anybody. We all worked on the aircraft together on detachment. We all loaded and worked like a tight little family. Rank had little meaning, we each had a job to do, did it and had fun.

Ultimately, while at the NARF, I was able to give a lot of input on the successor COD. This included having bigger engines and we finally got the APU plumbed internally, thank god. It had a better navigation suite, new props (which gave better range), lift devices on the leading edge which gave it a gross weight increase along with smoother flight performance. We couldn’t make it pretty, it was still so ugly you had to preflight it in a mirror. If you looked at it directly you would turn to stone.

I know for their peculiar reasons the Navy wants the V-22 Osprey to do the COD’s job now. I don’t see it. Engines were our primary hauling job and it simply can’t do it, the Osprey doesn't have enough cargo volume in the cabin. We had H-53s in our squadron as an experiment to do our job and it couldn’t do it either. The H-53 is a fabulous machine to fly, I’ve flown both the H-53D and H-53E, they are smooth powerful helicopters, but they are simply even less reliable than the C-2 and don’t have the range required for the COD mission. We used to refer to our H-53s as “mobile palm trees” Since they would go out to a remote location, break down, and we would rig a parachute over the rotor blades for shade to work on it. They also looked like a palm tree from the air.

A lot of different options have been suggested to work as C-2 replacements including the S-3 Fat Albert. It would work, but apparently it was far too expensive to re-engineer. It would have issues as well hauling the F-35’s engine.

Our limit on engines was the J79 with an afterburner attached. We couldn’t take a full fuel load with one loaded onboard. Aside from that, the method we loaded it was ludicrous. It was skid mounted and we had to drag it onboard with a winch we had mounted in the floor. The winch frequently broke, leading to rigging a cable with a snatch block out the airstair door and using a tow tractor to drag it on.

The military makes strange decisions. The COD replacement was chosen not by anybody with any experience in the COD community. No, it will be some guy with a lot of gold on his sleeve who probably flew pointy planes with lots of support people keeping him in the air. If he ever went someplace different, there was always cast of thousands keeping him flying. I do not think he or she has ever been in a sweaty, hydraulic oil stained flight suit on some remote airport, in some remote country, with a wrench in his hand helping get the moody POS back in the air.

I feel for the poor crew of that recently lost C-2. I know their terror. I wished it had worked out better for them. At least the majority of the folks got out of it alive, which is kind of a miracle in itself. The folks up front likely didn’t fare as well. Best wishes to them. I have only respect for what they did and how little the Navy in general respected them or supported them. We were the little people that kept the big machine working. If we didn’t do our job it couldn’t do its—well not forong at least.

USN

The fact is that the C-2 has a pretty impressive safety record, although according to one pilot who flew it in the 1980s, before the type was upgraded significantly it was anything but reliable and its critical mission lacked support, as well as appreciation, from the Navy.

James Wallace came to fly the C-2 at what is now viewed as something of a golden era for Naval Aviation. It was the early 1980s and the Cold War was in full swing. The Reagan Administration was executing a new form of foreign policy and backstopping it with massive defense spending. Still, the C-2 community didn't see much, or any, of this windfall according to Wallace, at least not early on. What he did experience was a neglected flying community infested with faulty officers and an airframe that was run-down and never really well prepared for its mission in the first place. And he almost paid for the aircraft's chronic deficiencies with his life.

But the unique carrier onboard delivery mission provided Wallace with an equally unique set of skills, namely how to operate on the fly from anywhere in the world with minimal support. He ended up turning these experiences, as well as his flight skills and his geology background, into a number of successful businesses, including Avior Technologies and Greystoke Leasing and Engineering, operating a wide number of aircraft in some of the toughest and most underdeveloped neighborhoods in the world. As James puts it:

"I really attribute my success and ability to work in war zones to the resourcefulness I learned flying the POS COD and its goofy mission. It made it so I am completely unfazed when things go wrong, terribly wrong, in an aircraft. I now have five complete engine failures, glide to landings in my career."

James Wallace's recollections remind us that the remodeled C-2s that are in need of replacement today are the product of some very tough lessons learned by those who flew their finicky and underpowered predecessors. It also underlines how critical the C-2's mission still is, regardless of the amount of attention it gets. This is especially important considering the Navy controversial plan to replace the Greyhound with V-22 Ospreys.

Here's James's story.

USN

Hitting the Greyhound trackFlying in the Navy is truly a real adventure. Well it was for those of us that entered the service as refugees from the final days of the “draft lottery.” I ended up in NROTC at UCLA in the early ’70s and it was a joy. Everybody hated and shunned us.

Well we finished up our degrees and most of us at UCLA got shunted off to the flight program. Being in those “tweener“ years before Regan took over, we got sent to Corpus Christi in the late ’70s to a flight program that was barely working. There we flew the last gasping T-28’s for our initial and intermediate flight training. We were supposed to transition to US-2B’s (the “Used To Be”) for our advanced flight training and carrier qualifications. The US-2B’s ended up being condemned just as we were being moved to the squadron. So in a fit of desperation the Navy got the T-44 for us to do advanced maritime multi-engine training. But there was one tiny problem—you can’t land a T-44 on the carrier.

We only had two prop aircraft that routinely landed on the carrier at the time, the C-2 Greyhound and E-2 Hawkeye. Both were absurdly expensive to operate and unsuitable for initial training of “nuggets” in the carrier environment. So they dusted off some T-28C models from the boneyard at Davis Monthan AFB and gave them a fresh coat of paint.

We qualified on the carrier in them and were last people to ever do single engine radials on a U.S. carrier. It was fairly useless training for us, as the radial single engine approach to landing on the carrier is a cut pass versus fly onto the deck pass. And we didn’t do catapult shots, we did deck runs for take off. However, it did carrier qualify us, but they would “enlighten” us later on at the RAG (replacement air group) on the proper way to do it.

I received my orders out of Corpus Christi to VR-24 to fly the Super COD out of Sigonella, Sicily via the RAG RVAW-120, who flew E-2s. Well, if I ever had any ambitions to have a career in the Navy, it ended there. There was no “career path” for a Carrier Onboard Delivery pilot.

This was immediately apparent when we got to the RAG, and were greeted with “oh, another COD puke.” We did our training in E-2C models, since the TE-2As were permanently un-serviceable, at least for the 11 months I was at the RAG.

Trust in CODThe E-2 is an unusual aircraft to fly, aside from its unusual looks. It was unstable in two axes. That made it a handful to fly and a joy to land on the carrier. Little did we know, the C-2 was unstable in all axes. So much so that the prototype killed the two Grumman test pilots during spin testing. This led to a big warning in the NATOPS manual: "Do not enter a spin.” As if I was going to try it out for fun one day with a load of cargo.

The C-2 and E-2 shared a common engine platform, the Allison T56. A fine engine—lots of power instantly available. It ran at a constant speed with a variation of -6 to +3.5 RPM. The core runs a gearbox via a shaft. Which in turn runs a propeller that is actually regulating the engine speed via a whole host of systems. First off the propeller is a separate hydraulically actuated and electronically controlled unit. This is protected by an auto feather system, a negative torque system, a pitch lock system, and finally a decoupling device to separate the engine from the gearbox.

Oh, this was a fun system to maintain, especially in the carrier environment. First off, the auto feather system would occasionally detect a power differential between the two engines via the Negative Torque System during a cat shot, leading to one of the engines feathering as you went down the cat track. You were usually at max gross weight when this happened making for a fun scramble to keep the aircraft flying and setting up for an air start when things settled down.

The engine, if for whatever reason it chose, due to a low RPM situation, would automatically shut down at 94% since the bleed valves would open and it would stop generating power.

The last fun failure was a pitch lock. This system was to keep the prop from over-speeding and would lock the props pitch setting at the last point it was operating at. This was our worst nightmare. If it happened at altitude, we would have what was in essence four giant speed brakes spinning on the wing, which would only get worse as we descended.

This happened to one of our C-2’s at Barcelona, Spain. The aircraft was virtually un-controllable on landing, unless there was arresting gear on the field. Barcelona didn’t have it and this led to a rather famous quote from the pilot: “I knew we were in trouble when the main landing gear passed us by.” It had ripped off the nacelle after going off the runway over a ditch. Un-believably, they re-worked that aircraft and gave it back to us, 18 months later.

The C-2, aside from being a paper napkin design born at a bar in Bethpage, New York was a very limited production aircraft. So much so that of the four we had one was the second prototype, still serving in the ’80s.

It was 1,000lbs heavier and mostly in the aft section. It even had its own set of maintenance manuals. It flew very differently than the other three, making it challenging if you had not flown it for a while or were taking it on the boat.

The C-2’s mission was very diverse and very critical to the Navy, which wasn’t reflected in how we were supported. The priority for logistical support is a hierarchy much like this: Pointy number one is fighters, then attack, then anti-submarine warfare (ASW), then electronic warfare (EW), then space aliens and pond slime and finally, oh yeah, the C-2 guys.

We had the same engine family as the E-2 but we had 650 less horsepower per side and operated 4,000lbs heavier. So we had a non-standard bastard stepchild engine that gave us no end of problems, and they were old, real old.

The aircraft had an auxiliary power unit (APU). Nice since the engines needed air for start. Well that APU only supplied air—no power, no hydraulics, just air. To make it worse, there wasn’t any associated plumbing. The crew had to plug a hose into the fuselage receptacle and run it to each engine in turn and plug the hose into the engine’s nacelle. Then un-plug it all roll it up and put it back in the airplane! What were they thinking!?

We always carried four cartons of Marlboros in our secret compartment to help us obtain an air start cart at remote airports. The lousy APU was anything but reliable.

Unglamorous but essentialThe Navy needs the C-2 to actually fight a war. We had two critical missions—supply engines for the carrier’s air wing as replacements and carry nukes back to the boat when they wanted to have nukes on them.

During war fighting, aircraft eat engines with foreign object debris (FOD) being the biggest problem. Apparently flying through the debris cloud caused by your attack on a ground target, or the randomly disintegrating aircraft you're fighting against, doesn’t do much good for a jet engine. We would be tasked to deliver two to four engines a day during combat to keep the air wing operational.

Then there was the other mission critical parts, the general stuff, from landing gear to rotor blades. We also had the capability to carry liquid oxygen (LOX) at 300 gallons a shot. This was a comical mission for us. We loaded on this huge skid mounted tank of LOX and we then connected its vent to on overboard vent. We had to wear parachutes when we flew with it onboard. Why? Who knows. If it failed in flight I suspect our first warning would have been the large explosion hurling aircraft bits and pieces of us in different directions.

We also carried personnel in 24 aft facing seats—four abreast facing aft with two tiny windows for one row to look out of. These poor souls would get to experience either a cat shot in a dark tube or a fun ride down to an arrested landing, in the dark. Frequently, you would look at the passengers (pax) shambling out white faced as they unloaded (we called pax, “self loading cargo”).

Our final and least critical mission, at least to the Navy, was carrying the mail. This was the most important to the ship’s crew and general morale. It was also fun for us as it made us modestly popular. Most of us sported USPS Letter Carrier patches on our flight suits. One of our aircraft even had a big sticker from a postal truck on the nose wheel door.

The postal mission seemed to be so important to the ship’s captain that we could use it as leverage. We were usually detached moving around at will for 30 days at a time. We would operate from someplace convenient, hit the ship and go to someplace else to spend the night. They didn’t like us to stay onboard the ship as we were too big and took up too much deck space. We took the break after the F-4s and F-14s landed so we could load and parked right behind the jet blast deflector on cat 1. We launched right after the fighters. It was rare we would spend a night onboard unless the weather was bad or we had mechanical issues. So normally we would get to shore and bed the aircraft down at night and go off to search out some seedy hotel that would be covered by our meager per diem rate.

On the road chasing carriersFrequently we wouldn’t get to bed until 10:00pm. We didn’t have time for dinner, we had to launch at sunup to make our overhead time above the carrier, which was frequently 300 to 400 miles offshore. So we rarely got meals and depended on our box lunches supplied by the carrier.

Well for whatever reason the air transfer officer (ATO) on the USS Independence thought this was some kind of joke (we hit virtually every carrier in the fleet, so rarely had any special relationship with one) and we got garbage in our box lunches. So after a few of these, “lunches” I took it up with the Air Boss. I explained that this was frequently our only meal of the day and my crew and I are living like gypsies with no support. So when I get back to, in this case Alexandria, Egypt, I am going to do a good walk around on the aircraft (I was the Airframes Division Officer). I will most likely write up around 80 gripes on this antique, whistling shitcan. So we will sit in Alexandria until somebody at the Smithsonian rounds up the parts and ships them to us so we can get back in the air. Then, maybe in a month or two, you will get your mail again!

We got much better meals after that, in fact, superb meals.

The C-2 had a large suite of comm gear, including a UHF—standard fare for carrier aircraft—a VHF Civilian com radio, and an HF with a 200 foot trailing wire. We would typically get our next day’s tasking via the HF from Air Services Coordination Mediterranean (ASCOMED) in Naples. We would vaguely know where the ship would be in 24 hours. They would give us a PIM—projected intended movement—the day before or occasionally we would get it from the local base or embassy in hard copy form. It was classified, so it was not transmitted via radio.

Well the damn boat never went where they told us it would be. This was unnerving since we could not refuel in flight and only had so much range. We frequently went out to the ship without the possibility of return to shore unless we refueled on the boat. Well we would navigate out to the boat with an OMEGA system, a now defunct long-range navigation system. This would get us to the general vicinity of the boat. We would then use our advanced Bendix black & white weather radar in map mode to find what looked like the battle group—a bunch of blips clustered around a big blip. Sometimes, the E-2 would be kind to us and give us vectors, but the carrier frequently operated in ENCOM—no radio communications.

It was a wonder we found them as frequently as we did. There were times I couldn’t locate the ship and I would transmit in the blind that we where turning back “with 4,000lbs of mail” and magically the E-2 or marshal controller onboard the carrier would answer us and give us vectors.

USNThe arrival of the COD means mail call for many sailors.

Our comm gear was one of the frequent failures. In Grumman’s infinite wisdom, they placed the VHF radios in the prop arc in a rack behind the cockpit. These were the same models used in the P-3 Orion. We really needed this radio, as we had to return to some civilian field someplace from Mombassa to Reykjavik. They tended to fail after the cat shot. So once, in my primate curiosity, I had the plane captain remove the box and bring it up to me in the cockpit. I was not going to try to get back to Athens NORDO (no radio).

I took out my swiss army knife and opened the box and found all the transistors rattling around in the box. Cleverly these were all socket-mounted and would eventually rattle loose. At least they all seemed to be the same part number and I plugged them back in. Magically this worked and became a standard post-cat shot procedure.

We did a lot of VIP flights. The Navy likes to do “dog and pony” shows for various bigwigs around the world. Normally, we had special seats for those flights. Special, being they where actually clean, not the normal hydraulic oil soaked ripped up POS’s we normally used.

You see we would go from all passengers to all cargo between lifts and have to un-track all the seats, stack them up and strap them down, build up the cargo cage and set up for cargo. This didn’t do much for the condition of the seats. I have personally taken folks such as ministers of defense of UK to President Mubarak of Egypt to the boat, along with all their entourage. We hated VIP lifts. They were a huge opportunity to screw up something and provided little praise or benefit to us.

One Air Force four star general took offense to my being so young, I was 23.5 years old and the plane commander. He wanted the much more seasoned older Lieutenant Commander, my co-pilot, to fly him out. I patiently explained that as a flag officer he can take command of the aircraft and do as he wishes. However the Lieutenant Commander here is not qualified to land this aircraft on the boat and I am feeling suddenly un-well and will stay ashore. My skipper commanded me to grow a beard to appear older.

Note the eagle lifting the engine can. This was the C-2's most important mission.

The "Elephant Graveyard"Our squadron, VR-24, was uniquely staffed and frequently referred to as the “Elephant Graveyard.” We had more commanders and lieutenant commanders than lieutenants. This was due to the following situation: If you screwed up someplace in the Navy but not enough to be kicked out, they sent you to us to get your 20 years in.

We also had some contract re-enters to fill up the roster as well. The problem was we could never get a boat deck to do their quals (carrier qualifications). So we only had four plane commanders to staff up 4 aircraft. Not too bad since we could only ever keep three of the aircraft even remotely airworthy at a time.

VR-24 also was unique in that it was a composite squadron. In addition to the C-2 we had a couple of C-1s (cargo variant of the S-2 Tracker), which were the last in the service and rarely went to the boat since there was no avgas on the boat. We also had T-39s (VIP Sabreliners jets), H-53Ds helicopters, and C-130s. So our squadron was actually several tiny squadrons in one.

The upside down distribution of senior officers led to a situation in that they had no ground job, and were referred to as “team pilots.” In other words they were there simply for flying and had no division or department head jobs. We never took them seriously and they tended not to give us any trouble, they were there to retire. It just made it awkward on detachment since the senior plane commander commanded the detachment.

We tended to have our usual crew which quickly became like family, just being the four of us for a month or two. Of course once one of the “elephants” had just joined the squadron, they didn’t get the relationship and would become offended when my crew would refer to me as “boss.” “He is a lieutenant in the US Navy” one of the new elephants shouted at my crewman, “you will call him SIR!” “OK, Boss Sir, what’s the plan for today?” I did mention we had no illusions as to our future careers in the Navy.

Resorting to the "alternative supply system"Our supply problems were so bad that our flight equipment was typically in tatters. Our squadron never had spare flight suits, gloves, sunglasses, boots and so on. We would have to use the “alternative supply system” to get our gear. This would include snatching up stacks of “Star and Strips” and taking them down to some supply chief on the boat and trading them for what we needed.

Frankly, we got quite a trading empire going to keep ourselves supplied. We would get whatever trade goods we could on shore—rugs, trinkets and such—to trade for gear—not booze, dear god we would go to prison for that. We would occasionally spirit one of our buds off the boat to spend the night onshore. This could have led to huge disciplinary issues if we had ever gotten caught.

We were discrete. We were on the bottom of the carrier pecking order, which runs downhill from fighters. One of my buds from flight school who was flying pointy planes, once talked to me on the boat on one of our rare overnight stays. He asked if it wasn’t humiliating to be stuck in such a POS aircraft. I replied “yes it isn’t the most glamorous thing to fly, but I’m going back to shore today to have a beer and talk it over with some chick in the bar back in Scotland.” Not living on the boat was refreshing.

I only had to do one four month deployment FLOATEX in the Indian Ocean. It was more or less a waste of time, since almost everyplace we could go was out of range. Once a week, the ship would steam over closer to Oman and we would fly over to Masirah, a small chunk of the moon that was offshore of Oman—not a single plant on that island. We would meet up with a C-141 and swap out whatever cargo and passengers we had.

Mostly we bored holes in the sky. They launched us everyday to get us off the deck. We would fly around randomly picking up ships on our weather radar and photographing them for the intel boys. We also took a load of folk off the carrier so they could get the experience of a flying off the boat. We would let them cycle through the co-pilot seat to get a decent view. This was a big reward for the hard working enlisted guys on the boat.

Saved by CyprusI had a large number of emergencies in the C-2, way more than any other aircraft I ever flew (76 different aircraft and helicopters by now). The aircraft were simply worn out, much like the fleet today.

My most memorable and one I am very thankful to be alive from occurred off Beirut. It was my first flight as a plane commander. At the 90 on final to land on the boat, I got a fire warning light on the left engine. I really didn’t have time to do anything but just land, the boat’s firefighting detail could deal with it. I trapped, made a call “COD’s on fire” and caged everything and we evacuated.

It turned out that a bleed air line had failed and the fire indicator was caused by hot air on the sensor. I was flying serial number 148148, the one unique C-2, it was the prototype and at that point 25 years old with nearly 50,000 hours on it. It was in a category beyond POS and started its life as an E-2. It was hacked and built into a C-2.

I launched off the next morning, deadhead—no pax or cargo—since it was a transfer back to base to complete the rest of the checks after the emergency. The cat shot was the normal thrill ride and we were climbing really fast as we were very light.

At around 15,000 feet I started to get an RPM TIT fluctuation on the left engine. I just happened to have the Allison tech representative on board, since he was going to check out the engines when we got back to shore. I said to myself, “oh fantastic, finally this engine is going to do it for him! Now perhaps he can finally see it and figure it out, once and for all.”

He come up forward and studied the engine and we do some tests with the prop control by switching to mechanical and to the fuel control out of electronic trim. Then the rep says “now I know what it is, you better shut it down, it's only going to get worse.” So we start to go through the precautionary engine shutdown procedure. A long list of switching things deliberately into the proper emergency configuration. Well we were down to the final item, fuel condition lever to shutdown-feather when the right engine fire warning started up.

There were flashing lights all over the board and the fire bell going off, just not on the left engine! Don’t second guess the system. I pushed the power back up on the left engine and reached over and pulled the right ’T’ handle. As soon as I pulled it the engine exploded and the aircraft rolled 60 degrees to the right—not what I expected. I must have pushed the extinguisher button 20 times but we still had very healthy flames coming out of the panels on the right engine nacelle, showing no indication the extinguisher did anything.

Well there is only so much you can do in the cockpit when things go to shit. I made my Mayday call on the radio with our position. The E-2 was vectoring folks to our position and kept us in sight. I did the last thing I could do when you're burning, I pushed the nose over and ran it up to redline—350kts—in an attempt to blow the fire out by providing more oxygen than the fire could burn. It doesn’t work by the way.

The air boss on the carrier was telling us to bail out, which if we had parachutes onboard that day we gladly would have. We normally didn’t carry them, passengers get so upset when you jump out and leave them behind. The C-2 had a beautiful bailout system. You pulled a handle and a section of the floor fell away, leaving a large hole to jump through—if you had a chute.

We were all terrified, as any sane person would be. The air boss told us to ditch, since we could not land on the boat—the deck was fouled and it would take too long to clear it for our return (we were the only launch of the day). I told the boss “not an option, we all die.” So I told the crew as we were passing 5,000 feet “I can try to make Cyprus, we may not make it, but we aren’t going to make it ditching, you know that.”

SAN DIEGO AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM148148 before its transformation from E-2 Hawkeye to C-2 Greyhound.

We headed to Akrotiri, 126 miles away—the longest 126 miles of my life. We were loosing power on the other engine the entire way and descending. We ended up in ground effect on the final approach to the runway. My hat is forever off to the fire crew at RAF Akrotiri, it was their day off and they manned up by the time we got there.

We did a landing—well kind of a landing—as I no longer had steering, just 12 applications of the brakes. We had no flaps and no arresting gear. I had to blow the landing gear down with the emergency air bottle as we were on emergency hydraulics. If I didn’t land there was no going around and I couldn’t get the gear back up anyways.

I was fast and more or less in limited control of the situation. Ultimately, to stay on the runway I blew both main tires braking differentially. By the time we stopped there was nothing left of the right main and the other main was a burning rim. We all jumped out of the aircraft’s various hatches and ran from the burning hulk with the fire crew spraying us and the aircraft.

I was running one way and one of the fire crew was running to the aircraft in a sliver suit. He had a giant asbestos blanket to wrap the burning main wheel and brake. They will blow up and red hot beryllium shrapnel shards will damage the fuel tank, which would make things so much worse. That firefighter had the biggest balls or the smallest brain of anybody I had seen to date.

After it all settled down I was really shaking and strangely really, really needed to take a leak. So I told the officer in charge there on the runway that I really needed to pee and I think my crew needs a drink. “No problem lads, we have a bar right here on the flight line, if you don’t mind warm beer!”

We ended up there for a month. It seemed we stumbled or bumbled into a secret squirrel operation the black hat guys had going on with a U-2 and its flights over the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. We seemed to have stirred up the press’s interest by going over the beach at 25 feet with apparently a bit of flame coming out of the engine. We were so sorry for ruining their day and honestly would have gone someplace else, had we known. Actually, they threw us a party a couple days later and gave us their T shirts that said, “IF WE’RE NOT HERE, WHERE THE HELL ARE WE?” Even the spooks have a sense of humor.

Since we where stuck there, we naturally had lots of time on our hands awaiting engines and gear and a bunch of parts. They couldn’t just drop the stuff off. We had to send messages up to the Brits, who would walk it over to CINAVEUR who would send it to the squadron. Then the stuff had to ship to England so they could transport it on a RAF aircraft to Akrotiri. It took forever. Well there was a junkyard of all the UN vehicles from Palestine—mine casualties and such. I drove a Land Rover Series III in Sicily. Well Land Rovers always need parts, so I scavenged a bunch of bits and pieces, including a gear shift lever.

When we finally got back to Italy, my wife came to pick me up in the Land Rover. Well the gear shifter broke off while she was pulling into the parking lot. Some of the other pilots pushed her into the space and she came out to meet me on the flight line. She was not super happy about this and she greets me with the gear shifter in her hand. I reach in my parachute bag and pull out a new one."See not a problem." Which she replied “you knew it was going to break!”

We actually fixed up 148148 well enough to fly it back to Sigonella in Italy after a month where it was completely repaired and soldiered on for a few more years until the next generation C-2s took over. I hope it is gracing a pole in front of some airport someplace. I still have a model of it on my shelf in my office.

The NARF crew at NAS North Island while James was a test pilot there.

Reflecting back and looking towards the futureWhen I got back, my skipper was proud of me, not dying and all. He told me he knew a lot of “really good pilots, but very few lucky pilots.” He said “you my boy are the luckiest one I know.” He ultimately got me my orders as the program manager and test pilot for the E-2 and C-2 at the Naval Air Rework Facility (NARF). He knew I had no intention of staying in the Navy and he told me that going in the Aviation Engineering Duty Officer route was a career dead end, but was the best possible job if you got out. It was, I ended up transferring my commission to NOAA and doing research flying for a few years.

The NARF trained me to fly a whole host of aircraft and helicopters and under some pretty intense circumstances. Most fleet guys almost never get to do a field arrestment. I did one almost once, and even sometimes twice a week. I had one string of flights that I did one every day. The NARF at NAS Alameda did the prop controls for the P-3, E-2, C130 and such. There were four guys in the shop, the oldest one retired and I received a string of seven bad prop controls, with one aircraft getting two. I did a precautionary shutdown on one engine and was on approach for an arrestment. At about 50 feet the remaining engine flamed out when the RPM dropped below 94 percent. I hit hard, real hard, but luckily caught the wire. I blew both tires and fragged the mains. Fouled the runway for about eight hours that day while they hunted around for the special rigging to pick the airplane up with a crane. The crash crew loved me.

In between NARF and NOAA I worked at Electrospace doing kind of the same thing I did at the NARF, but I was Special Mission Systems Program Manager, which paid a whole lot better. We built one-offs for various agencies and did the weird electronic warfare (EW) aircraft like refitting the A-3’s for jamming, special EW DC8s, Citations, Cheyennes and foreign aircraft like Super Mystères for South American customers. I took the job with NOAA—they sought me out—as they wanted a geologist and I was a safety school graduate who could fly anything they had. In the year before I got there they had 12 accidents with 18 pilots on staff! Well NOAA stands for No Organization At All. After 3 years, I left and started my own thing and never looked back.

I became an owner operator of a host of aircraft and repair stations in some various unique places. I still look back to my COD puke days as the most fun a 20 year old could have, with a few moments of terror thrown in.

The aircraft were horrible but the flying off of the boat and being left to our own devices all over the world was a hoot. We learned how to get into any country and deal with whatever we needed to on the ground without any support from anybody. We all worked on the aircraft together on detachment. We all loaded and worked like a tight little family. Rank had little meaning, we each had a job to do, did it and had fun.

Ultimately, while at the NARF, I was able to give a lot of input on the successor COD. This included having bigger engines and we finally got the APU plumbed internally, thank god. It had a better navigation suite, new props (which gave better range), lift devices on the leading edge which gave it a gross weight increase along with smoother flight performance. We couldn’t make it pretty, it was still so ugly you had to preflight it in a mirror. If you looked at it directly you would turn to stone.

I know for their peculiar reasons the Navy wants the V-22 Osprey to do the COD’s job now. I don’t see it. Engines were our primary hauling job and it simply can’t do it, the Osprey doesn't have enough cargo volume in the cabin. We had H-53s in our squadron as an experiment to do our job and it couldn’t do it either. The H-53 is a fabulous machine to fly, I’ve flown both the H-53D and H-53E, they are smooth powerful helicopters, but they are simply even less reliable than the C-2 and don’t have the range required for the COD mission. We used to refer to our H-53s as “mobile palm trees” Since they would go out to a remote location, break down, and we would rig a parachute over the rotor blades for shade to work on it. They also looked like a palm tree from the air.

A lot of different options have been suggested to work as C-2 replacements including the S-3 Fat Albert. It would work, but apparently it was far too expensive to re-engineer. It would have issues as well hauling the F-35’s engine.

Our limit on engines was the J79 with an afterburner attached. We couldn’t take a full fuel load with one loaded onboard. Aside from that, the method we loaded it was ludicrous. It was skid mounted and we had to drag it onboard with a winch we had mounted in the floor. The winch frequently broke, leading to rigging a cable with a snatch block out the airstair door and using a tow tractor to drag it on.

The military makes strange decisions. The COD replacement was chosen not by anybody with any experience in the COD community. No, it will be some guy with a lot of gold on his sleeve who probably flew pointy planes with lots of support people keeping him in the air. If he ever went someplace different, there was always cast of thousands keeping him flying. I do not think he or she has ever been in a sweaty, hydraulic oil stained flight suit on some remote airport, in some remote country, with a wrench in his hand helping get the moody POS back in the air.

I feel for the poor crew of that recently lost C-2. I know their terror. I wished it had worked out better for them. At least the majority of the folks got out of it alive, which is kind of a miracle in itself. The folks up front likely didn’t fare as well. Best wishes to them. I have only respect for what they did and how little the Navy in general respected them or supported them. We were the little people that kept the big machine working. If we didn’t do our job it couldn’t do its—well not forong at least.

USN

Perspectives on the Coming of the CMV-22B to the Large Deck Carrier

By Mr. Robbin Laird

I first viewed a CMV-22B in person when attending the Reveal ceremony in Amarillo, Texas held on February 6, 2020. But I am no stranger to the Osprey having seen my first Ospreys at Second Marine Air Wing in 2007. At that time there were four Ospreys on the tarmac.

The plane has come a long way since then, with the Marines taking it in to every clime and place with the transformational aircraft having a significant change on how the Marines operate. Now the plane is coming in a modified form to the U.S. Navy, as it is technically replacing the C-2 Greyhound in its carrier support role.

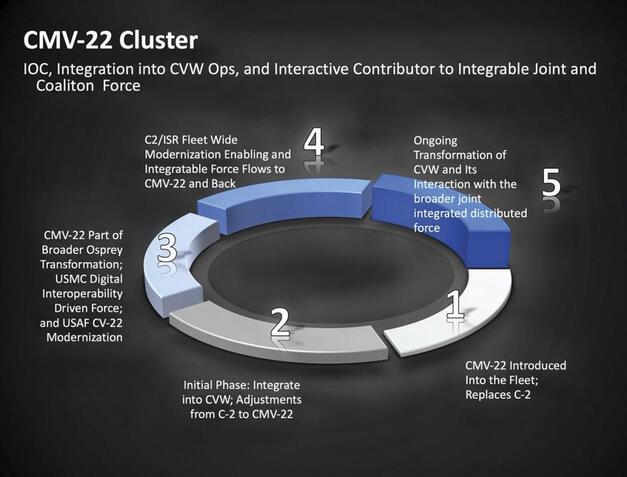

Nonetheless, the CMV-22B is no more a replacement for the C-2 Greyhound, than the MV-22 was for the CH46. The MV-22 covered the functions of the CH-46 for the Marine Corps but represented a disruptive change; it has driven transformation of the USMC and its operations. The CMV-22B will be part of a very significant change in the carrier air wing, as it is part of a new generation of assets to operate from the large deck carrier.

This is a shift from what I call the integrated to the integratable air wing; whereas a new asset to the large deck carrier historically has been integrated into the air wing, with the coming of the Osprey, the MQ-25, the F-35C, the Advanced Hawkeye and other assets, the air wing is expanding its reach to work with assets on other ships and non-US combat assets to deliver the combat effect of the air wing.

What is being set in motion is a new approach where each new platform which comes into the force might be considered at the center of a cluster of changes. The change is not just about integrating a new platform in the flight ops of the carrier. The change is also about how the new platform affects what one can do with adjacent assets in the CSG or how to integrate with adjacent U.S. or allied combat platforms, forces, and capabilities. What is being shaped is an interactive kill web approach whereby assets coming off of the carrier can intersect with assets not organic to the carrier to expand the reach of any particular air asset from the carrier air wing, and to enhance that platform’s contribution to the joint fight.

An example of this dynamic was highlighted by the addition of air refueling for the Advanced Hawkeye. Recently, VAW126 Seahawks became the first Advanced Hawkeye squadron to qualify its pilots for air refueling. The focus of the press on this development has been upon how the reach of the Advance Hawkeye has been enhanced. Although true, that misses an important contribution of expanded reach and duration for the entire fleet, and the joint force, not just for the carrier air wing.

For example, the Marines are shaping answers to this question: How can the Marines contribute most effectively to the core Navy mission of sea denial and sea control? Part of the answer is to expand the role of the amphibious fleet and its onboard Marine Corps air and ground capability to play a key role in this mission. An Advanced Hawkeye can augment the ability of this fleet to do this mission and with the extended range with air refueling of the Hawkeye plus the coming of the MQ-25 to the large deck carrier to do that air refueling mission, the prospects of leveraging the capability of a member of the integratable air wing to provide ISR/C2 support for the amphibious task force is enhanced.

The CMV-22 is joining the Air Wing in the process of the integratable revolution. And further discussions, with the participants in the coming of the CMV-22B to the large carrier provided further insights into the process.

Last Fall, I went to Naval Air Station Patuxent River and to meet with Col Matthew Kelly, who is in charge of the V-22 Joint Program Office (PMA-275). We discussed the next phase of Osprey development. The U.S. Navy is joining Osprey Nation at the same time as the Japanese. As Col. Kelly commented: “There is no other air platform that has the breadth of aircraft laydown across the world than does the V-22. And now that breadth is expanding with the inclusion of the carrier fleet and the Japanese. We currently have a sustainment system which works but we need to make it better in terms of supporting global operations.”

The plane has come a long way since then, with the Marines taking it in to every clime and place with the transformational aircraft having a significant change on how the Marines operate. Now the plane is coming in a modified form to the U.S. Navy, as it is technically replacing the C-2 Greyhound in its carrier support role.

Nonetheless, the CMV-22B is no more a replacement for the C-2 Greyhound, than the MV-22 was for the CH46. The MV-22 covered the functions of the CH-46 for the Marine Corps but represented a disruptive change; it has driven transformation of the USMC and its operations. The CMV-22B will be part of a very significant change in the carrier air wing, as it is part of a new generation of assets to operate from the large deck carrier.

This is a shift from what I call the integrated to the integratable air wing; whereas a new asset to the large deck carrier historically has been integrated into the air wing, with the coming of the Osprey, the MQ-25, the F-35C, the Advanced Hawkeye and other assets, the air wing is expanding its reach to work with assets on other ships and non-US combat assets to deliver the combat effect of the air wing.

What is being set in motion is a new approach where each new platform which comes into the force might be considered at the center of a cluster of changes. The change is not just about integrating a new platform in the flight ops of the carrier. The change is also about how the new platform affects what one can do with adjacent assets in the CSG or how to integrate with adjacent U.S. or allied combat platforms, forces, and capabilities. What is being shaped is an interactive kill web approach whereby assets coming off of the carrier can intersect with assets not organic to the carrier to expand the reach of any particular air asset from the carrier air wing, and to enhance that platform’s contribution to the joint fight.

An example of this dynamic was highlighted by the addition of air refueling for the Advanced Hawkeye. Recently, VAW126 Seahawks became the first Advanced Hawkeye squadron to qualify its pilots for air refueling. The focus of the press on this development has been upon how the reach of the Advance Hawkeye has been enhanced. Although true, that misses an important contribution of expanded reach and duration for the entire fleet, and the joint force, not just for the carrier air wing.

For example, the Marines are shaping answers to this question: How can the Marines contribute most effectively to the core Navy mission of sea denial and sea control? Part of the answer is to expand the role of the amphibious fleet and its onboard Marine Corps air and ground capability to play a key role in this mission. An Advanced Hawkeye can augment the ability of this fleet to do this mission and with the extended range with air refueling of the Hawkeye plus the coming of the MQ-25 to the large deck carrier to do that air refueling mission, the prospects of leveraging the capability of a member of the integratable air wing to provide ISR/C2 support for the amphibious task force is enhanced.

The CMV-22 is joining the Air Wing in the process of the integratable revolution. And further discussions, with the participants in the coming of the CMV-22B to the large carrier provided further insights into the process.

Last Fall, I went to Naval Air Station Patuxent River and to meet with Col Matthew Kelly, who is in charge of the V-22 Joint Program Office (PMA-275). We discussed the next phase of Osprey development. The U.S. Navy is joining Osprey Nation at the same time as the Japanese. As Col. Kelly commented: “There is no other air platform that has the breadth of aircraft laydown across the world than does the V-22. And now that breadth is expanding with the inclusion of the carrier fleet and the Japanese. We currently have a sustainment system which works but we need to make it better in terms of supporting global operations.”

After Pax River, my next discussion of the coming of the CV-22B was with the Navy’s Air Boss, Vice Admiral Miller. In a meeting in his office in San Diego a week before attending the reveal ceremony on February 6, 2020 in Amarillo Texas. We discussed how the Air Wing was changing, and the impact of the coming of new platforms, like the CMV-22B. We agreed that a way to look at the way ahead was not so much the integrated air wing, but the shaping of the integratable air wing.