US Navy, Boeing Complete 1st Carrier Tests for MQ-25

Using a new remote-controlled system, the Boeing-owned unmanned T1 test asset easily and efficiently moved about the aircraft carrier deck - demonstrating the capability of the MQ-25

The U.S. Navy and Boeing [NYSE: BA] have successfully maneuvered the Boeing-owned T1 test asset on a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier for the first time – an early step forward in ensuring the MQ-25 unmanned aerial refueler will seamlessly integrate into carrier operations. During an underway demonstration aboard the USS George H.W. Bush (CVN 77), Navy flight deck directors – known as “yellow shirts” – used standard hand signals to direct T1 just like any other carrier-based aircraft. Instead of a pilot receiving the commands, however, it was a Boeing MQ-25 Deck Handling Operator (DHO) right beside the “yellow shirt” who commanded the aircraft using a new handheld deck control device.

“This is another significant step forward in demonstrating MQ-25’s integration into the Carrier Air Wing on the flight deck of our Fleet’s aircraft carriers,” said Capt. Chad Reed, Unmanned Carrier Aviation program manager. “The success of this event is a testament to the hard work of our engineers, testers, operators and the close collaboration and teaming from Naval Air Force Atlantic and the crew aboard CVN 77.”

The demonstration was intended to ensure the design of the MQ-25 will successfully integrate into the carrier environment and to evaluate the functionality, capability and handling qualities of the deck handling system both in day and night conditions. Maneuvers included taxiing on the deck, connecting to the catapult, clearing the landing area and parking on the deck.

“The Navy has a rigorous, well-established process for moving aircraft on the carrier. Our goal was to ensure the MQ-25 fits into the process without changing it,” said Jim Young, MQ-25 chief engineer. “From the design of the aircraft to the design of the system moving it, our team has worked hard to make the MQ-25 carrier suitable in every way.”

DHO’s trained in Boeing’s deck handling simulation lab in St. Louis, where they practiced entering commands from simulated “yellow shirts” into the real handheld device. A simulated MQ-25, running the aircraft’s real operational flight code and interfaces, would move accordingly. The handheld controller is a simple, easy-to-use device designed specifically for a generation of sailors who natively understand such handheld technology and have experience with controllers used in the gaming industry today.

The deck handling demonstration followed a two-year flight test campaign for the Boeing-owned T1 test asset, during which the Boeing and Navy team refueled three different carrier-based aircraft – an F/A-18 Super Hornet, an E-2D Hawkeye and an F-35C Lightning II.

“The Navy gave us two key performance parameters for the program – aerial refueling and integration onto the carrier deck,” said Dave Bujold, Boeing MQ-25 program director. “We’ve shown that the MQ-25 can meet both requirements, and we’ve done it years earlier than traditional acquisition programs.”

Source: Boeing

Date: Dec 20, 2021

“This is another significant step forward in demonstrating MQ-25’s integration into the Carrier Air Wing on the flight deck of our Fleet’s aircraft carriers,” said Capt. Chad Reed, Unmanned Carrier Aviation program manager. “The success of this event is a testament to the hard work of our engineers, testers, operators and the close collaboration and teaming from Naval Air Force Atlantic and the crew aboard CVN 77.”

The demonstration was intended to ensure the design of the MQ-25 will successfully integrate into the carrier environment and to evaluate the functionality, capability and handling qualities of the deck handling system both in day and night conditions. Maneuvers included taxiing on the deck, connecting to the catapult, clearing the landing area and parking on the deck.

“The Navy has a rigorous, well-established process for moving aircraft on the carrier. Our goal was to ensure the MQ-25 fits into the process without changing it,” said Jim Young, MQ-25 chief engineer. “From the design of the aircraft to the design of the system moving it, our team has worked hard to make the MQ-25 carrier suitable in every way.”

DHO’s trained in Boeing’s deck handling simulation lab in St. Louis, where they practiced entering commands from simulated “yellow shirts” into the real handheld device. A simulated MQ-25, running the aircraft’s real operational flight code and interfaces, would move accordingly. The handheld controller is a simple, easy-to-use device designed specifically for a generation of sailors who natively understand such handheld technology and have experience with controllers used in the gaming industry today.

The deck handling demonstration followed a two-year flight test campaign for the Boeing-owned T1 test asset, during which the Boeing and Navy team refueled three different carrier-based aircraft – an F/A-18 Super Hornet, an E-2D Hawkeye and an F-35C Lightning II.

“The Navy gave us two key performance parameters for the program – aerial refueling and integration onto the carrier deck,” said Dave Bujold, Boeing MQ-25 program director. “We’ve shown that the MQ-25 can meet both requirements, and we’ve done it years earlier than traditional acquisition programs.”

Source: Boeing

Date: Dec 20, 2021

US Navy, Boeing Conduct 1st MQ-25 Refueling Mission with F-35C

Unmanned MQ-25 T1 test asset refuels a third U.S. Navy carrier-basedaircraft, demonstrating the maturity of the aircraft's design and performance

The U.S. Navy and Boeing [NYSE: BA] have used the MQ-25TM T1 test asset to refuel a U.S. Navy F-35C Lightning II fighter jet for thefirst time, once again demonstrating the aircraft’s ability to achieve its primary aerial refueling mission.

This was the third refueling mission for the Boeing-owned test asset in just over three months, advancing the test program for the Navy’s first operational carrier-based unmanned aircraft. T1 refueled an F/A-18 Super Hornet in June and an E-2D Hawkeye in August.

“Every test flight with another Type/Model/Series aircraft gets us one step closer to rapidly delivering a fully mission-capable MQ-25 to the fleet,” said Capt. Chad Reed, the Navy’s Unmanned Carrier Aviation program manager. “Stingray’s unmatched refueling capability is going to increase the Navy’s power projection and provide operational flexibility to the Carrier Strike Group commanders.”

The U.S. Navy and Boeing [NYSE: BA] have used the MQ-25TM T1 test asset to refuel a U.S. Navy F-35C Lightning II fighter jet for thefirst time, once again demonstrating the aircraft’s ability to achieve its primary aerial refueling mission.

This was the third refueling mission for the Boeing-owned test asset in just over three months, advancing the test program for the Navy’s first operational carrier-based unmanned aircraft. T1 refueled an F/A-18 Super Hornet in June and an E-2D Hawkeye in August.

“Every test flight with another Type/Model/Series aircraft gets us one step closer to rapidly delivering a fully mission-capable MQ-25 to the fleet,” said Capt. Chad Reed, the Navy’s Unmanned Carrier Aviation program manager. “Stingray’s unmatched refueling capability is going to increase the Navy’s power projection and provide operational flexibility to the Carrier Strike Group commanders.”

MQ-25 Stingray T1 test asset refuels an E-2D aircraft Aug. 18, 2021, at MidAmerica Airport in Illinois. Boeing Photo

Boeing’s prototype for the Navy’s first unmanned aerial tanker successfully refueled its second aircraft type in a test over Illinois, the service announced on Thursday.

The MQ-25 T1 prototype topped off an E-2D Advanced Hawkeye flown by the in a series of test flights from MidAmerica Airport in Mascoutah, Ill., just outside of St. Louis.

“During the six-hour flight, Navy E-2D pilots from Air Test and Evaluation Squadron Two Zero (VX) 20 approached T1, performed formation evaluations, wake surveys, drogue tracking and plugs with the MQ-25 test asset at 220 knots calibrated airspeed (KCAS) and 10,000 feet,” according to a release from Naval Air Systems Command.

“This test allows the program to analyze the aerodynamic interaction of the two aircraft. The team can then determine if any adjustments to guidance and control are required and make those software updates early, with no impact to the developmental test schedule.”

The promise for the E-2D, now equipped with an aerial refueling capability, is to stay aloft longer for better awareness around the carrier strike group.

The Wednesday flight follows a June test between the prototype and a Super Hornet to prove the initial concept that the T1 – built by Boeing in 2014 as the company’s bid for the canceled Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) program – could handle the refueling mission. The prototype initially flew with the refueling configuration in December of 2019.

“T1 testing will continue over the next several months to include flight envelope expansion, engine testing, and deck handling demonstrations aboard an aircraft carrier before the MQ-25 engineering, manufacturing and development aircraft are delivered next year,” NAVAIR said in a statement.

The goal for the program is to deliver up to 15,000 pounds of fuel up to 500 nautical miles from the carrier, USNI News reported in 2017. Eventually, the Navy’s plan is to integrate the MQ-25As with the C-2 and E-2D communities as part of the Navy’s larger manned-unmanned teaming construct for UAVs.

“The Navy will begin standing up the fleet replacement squadron, Unmanned Carrier-Launched Multi Role Squadron (VUQ) 10, later this year followed by two MQ-25A squadrons, VUQ-11 and 12. These squadrons will deploy detachments to the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers,” NAVAIR said on Thursday.

For now, the mission for the MQ-25A is to relieve the Super Hornet fleet of the aerial refueling burden which can account for 20 to 30 percent of flight hours for an operational air wing, USNI News understands.

The Navy is considering expanding the mission set to include information, surveillance and reconnaissance roles more in line with the original vision for the UCLASS program.

In Thursday’s statement, NAVAIR played up the ISR role for the aircraft to be, “the eyes and ears of the fleet will now be able to provide up-to-the-minute information from deep within theater to facilitate rapid-decision making by carrier strike group leadership,” reads the statement.

The first engineering developmental models are scheduled to arrive next year as part of a 2018 award to Boeing for $805-million contract to build the first four MQ-25As.

Boeing’s prototype for the Navy’s first unmanned aerial tanker successfully refueled its second aircraft type in a test over Illinois, the service announced on Thursday.

The MQ-25 T1 prototype topped off an E-2D Advanced Hawkeye flown by the in a series of test flights from MidAmerica Airport in Mascoutah, Ill., just outside of St. Louis.

“During the six-hour flight, Navy E-2D pilots from Air Test and Evaluation Squadron Two Zero (VX) 20 approached T1, performed formation evaluations, wake surveys, drogue tracking and plugs with the MQ-25 test asset at 220 knots calibrated airspeed (KCAS) and 10,000 feet,” according to a release from Naval Air Systems Command.

“This test allows the program to analyze the aerodynamic interaction of the two aircraft. The team can then determine if any adjustments to guidance and control are required and make those software updates early, with no impact to the developmental test schedule.”

The promise for the E-2D, now equipped with an aerial refueling capability, is to stay aloft longer for better awareness around the carrier strike group.

The Wednesday flight follows a June test between the prototype and a Super Hornet to prove the initial concept that the T1 – built by Boeing in 2014 as the company’s bid for the canceled Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) program – could handle the refueling mission. The prototype initially flew with the refueling configuration in December of 2019.

“T1 testing will continue over the next several months to include flight envelope expansion, engine testing, and deck handling demonstrations aboard an aircraft carrier before the MQ-25 engineering, manufacturing and development aircraft are delivered next year,” NAVAIR said in a statement.

The goal for the program is to deliver up to 15,000 pounds of fuel up to 500 nautical miles from the carrier, USNI News reported in 2017. Eventually, the Navy’s plan is to integrate the MQ-25As with the C-2 and E-2D communities as part of the Navy’s larger manned-unmanned teaming construct for UAVs.

“The Navy will begin standing up the fleet replacement squadron, Unmanned Carrier-Launched Multi Role Squadron (VUQ) 10, later this year followed by two MQ-25A squadrons, VUQ-11 and 12. These squadrons will deploy detachments to the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers,” NAVAIR said on Thursday.

For now, the mission for the MQ-25A is to relieve the Super Hornet fleet of the aerial refueling burden which can account for 20 to 30 percent of flight hours for an operational air wing, USNI News understands.

The Navy is considering expanding the mission set to include information, surveillance and reconnaissance roles more in line with the original vision for the UCLASS program.

In Thursday’s statement, NAVAIR played up the ISR role for the aircraft to be, “the eyes and ears of the fleet will now be able to provide up-to-the-minute information from deep within theater to facilitate rapid-decision making by carrier strike group leadership,” reads the statement.

The first engineering developmental models are scheduled to arrive next year as part of a 2018 award to Boeing for $805-million contract to build the first four MQ-25As.

Fueling the Future: MQ-25 first to conduct unmanned aerial tanking

Published:

June 7, 2021

The MQ-25 T1 test asset refuels a Navy F/A-18 during a flight June 4 at MidAmerica Airport in Illinois. This flight demonstrated that the MQ-25 Stingray can fulfill its tanker mission using the Navy’s standard probe-and-drogue aerial refueling method. (Photo courtesy of Boeing)

NAVAL AIR SYSTEMS COMMAND, PATUXENT RIVER, Md.

--

The MQ-25™ program successfully conducted the first ever aerial refueling operations between a manned receiver aircraft and unmanned tanker June 4 from MidAmerica Airport in Mascoutah, Illinois.

This successful flight demonstrated that the MQ-25 Stingray can fulfill its tanker mission using the Navy’s standard probe-and-drogue aerial refueling method.

“This flight lays the foundation for integration into the carrier environment, allowing for greater capability toward manned-unmanned teaming concepts,” said Rear Adm. Brian Corey who oversees the Program Executive Office for Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons. “MQ-25 will greatly increase the range and endurance of the future carrier air wing – equipping our aircraft carriers with additional assets well into the future.”

During the flight, the receiver Navy F/A-18 Super Hornet approached the Boeing-owned MQ-25 T1 test asset, conducted a formation evaluation, wake survey, drogue tracking and then plugged with the unmanned aircraft. T1 then successfully transferred fuel from its Aerial Refueling Store (ARS) to the F/A-18.

“This is our mission, an unmanned aircraft that frees our strike fighters from the tanker role, and provides the Carrier Air Wing with greater range, flexibility and capability,” said Capt. Chad Reed, program manager for the Navy’s Unmanned Carrier Aviation program office (PMA-268). “Seeing the MQ-25 fulfilling its primary tasking today, fueling an F/A-18, is a significant and exciting moment for the Navy and shows concrete progress toward realizing MQ-25’s capabilities for the fleet.”

The test flight will provide important early data on airwake interactions, as well as guidance and control, Reed said. The team will analyze that data to determine if any adjustments are needed and make software updates early, with no impact to the program’s test schedule.

Testing with T1 will continue over the next several months to include flight envelope expansion, engine testing, and deck handling demonstrations aboard an aircraft carrier later this year.

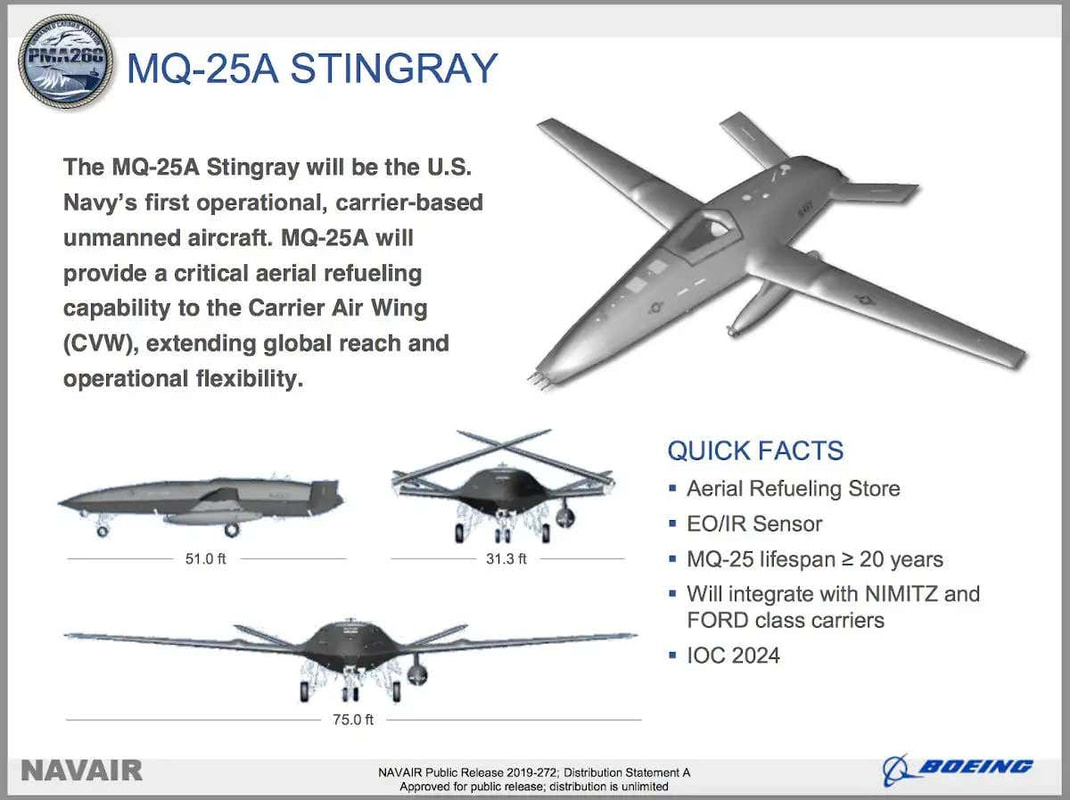

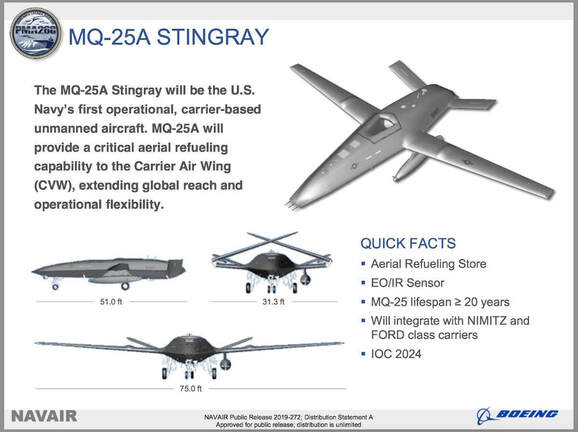

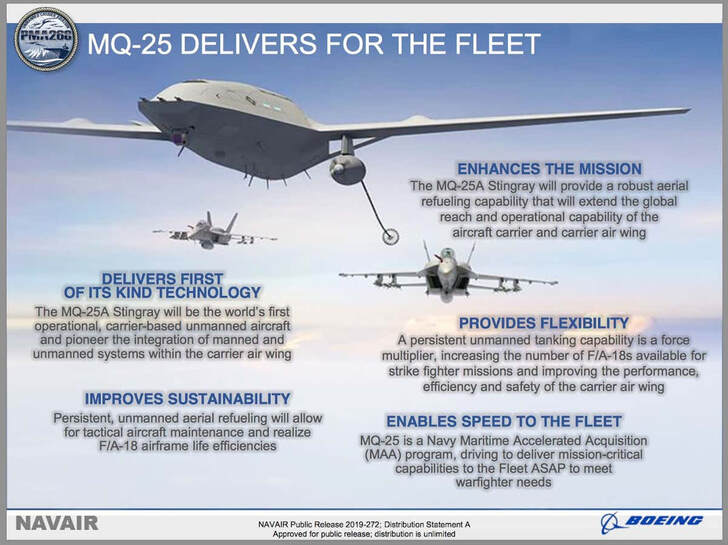

The MQ-25A Stingray will be the world’s first operational carrier-based unmanned aircraft and provide critical aerial refueling and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities that greatly expand the global reach, operational flexibility and lethality of the carrier air wing and carrier strike group. The MQ-25 is foundational to the Navy’s Unmanned Campaign Framework and is the first step toward a future fleet augmented by unmanned systems to pace the evolving challenges of the 21st century.

MQ-25 and Stingray are trademarks of the Department of the Navy.

The MQ-25 T1 test asset refuels a Navy F/A-18 during a flight June 4 at MidAmerica Airport in Illinois. This flight demonstrated that the MQ-25 Stingray can fulfill its tanker mission using the Navy’s standard probe-and-drogue aerial refueling method. (Photo courtesy of Boeing)

Public Affairs Officer Contact:

240-925-5305

--

The MQ-25™ program successfully conducted the first ever aerial refueling operations between a manned receiver aircraft and unmanned tanker June 4 from MidAmerica Airport in Mascoutah, Illinois.

This successful flight demonstrated that the MQ-25 Stingray can fulfill its tanker mission using the Navy’s standard probe-and-drogue aerial refueling method.

“This flight lays the foundation for integration into the carrier environment, allowing for greater capability toward manned-unmanned teaming concepts,” said Rear Adm. Brian Corey who oversees the Program Executive Office for Unmanned Aviation and Strike Weapons. “MQ-25 will greatly increase the range and endurance of the future carrier air wing – equipping our aircraft carriers with additional assets well into the future.”

During the flight, the receiver Navy F/A-18 Super Hornet approached the Boeing-owned MQ-25 T1 test asset, conducted a formation evaluation, wake survey, drogue tracking and then plugged with the unmanned aircraft. T1 then successfully transferred fuel from its Aerial Refueling Store (ARS) to the F/A-18.

“This is our mission, an unmanned aircraft that frees our strike fighters from the tanker role, and provides the Carrier Air Wing with greater range, flexibility and capability,” said Capt. Chad Reed, program manager for the Navy’s Unmanned Carrier Aviation program office (PMA-268). “Seeing the MQ-25 fulfilling its primary tasking today, fueling an F/A-18, is a significant and exciting moment for the Navy and shows concrete progress toward realizing MQ-25’s capabilities for the fleet.”

The test flight will provide important early data on airwake interactions, as well as guidance and control, Reed said. The team will analyze that data to determine if any adjustments are needed and make software updates early, with no impact to the program’s test schedule.

Testing with T1 will continue over the next several months to include flight envelope expansion, engine testing, and deck handling demonstrations aboard an aircraft carrier later this year.

The MQ-25A Stingray will be the world’s first operational carrier-based unmanned aircraft and provide critical aerial refueling and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities that greatly expand the global reach, operational flexibility and lethality of the carrier air wing and carrier strike group. The MQ-25 is foundational to the Navy’s Unmanned Campaign Framework and is the first step toward a future fleet augmented by unmanned systems to pace the evolving challenges of the 21st century.

MQ-25 and Stingray are trademarks of the Department of the Navy.

The MQ-25 T1 test asset refuels a Navy F/A-18 during a flight June 4 at MidAmerica Airport in Illinois. This flight demonstrated that the MQ-25 Stingray can fulfill its tanker mission using the Navy’s standard probe-and-drogue aerial refueling method. (Photo courtesy of Boeing)

Public Affairs Officer Contact:

240-925-5305

Navy Prepares For Integration Of MQ-25 Tanker Drones With E-2 Hawkeye Squadrons The MQ-25s will be attached to E-2 squadrons during deployments and Hawkeye crews will cross-train to also fly the Stingrays.

BY JOSEPH TREVITHICK NOVEMBER 3, 2020

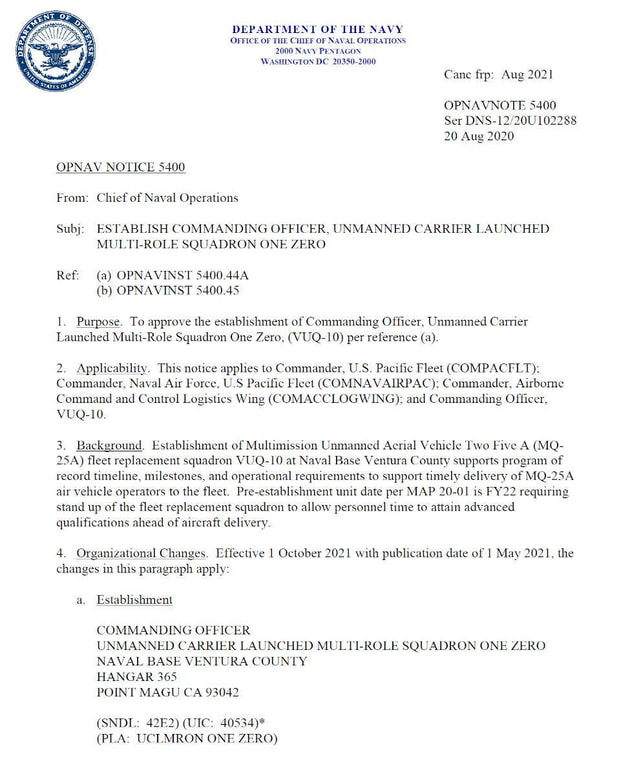

The U.S. Navy has revealed more details about its plans for its future fleet of Boeing MQ-25A Stingray tanker drones and how it will integrate them into its carrier air wings attached to squadrons flying the E-2C/D Hawkeye airborne command and control aircraft. This comes as the service is working to stand up its first MQ-25A unit, Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10, or VUQ-10.

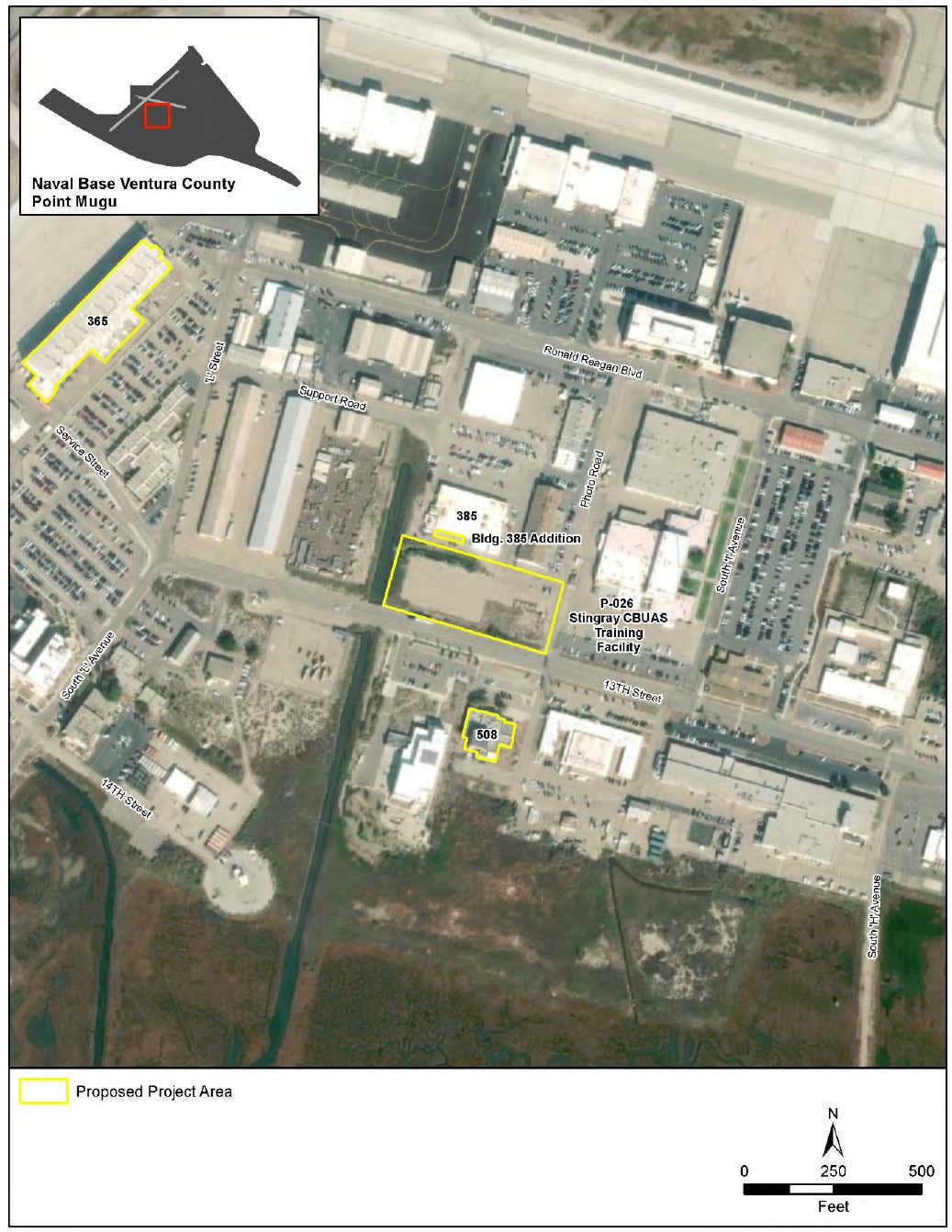

The new information comes from a draft environmental impact assessment regarding the construction of new facilities at Naval Base Ventura County, in Point Mugu, California, which the Navy posted online recently. These kinds of assessments are a routine part of the process of approving major new additions to U.S. military bases, which also includes input from various other federal, state, and local stakeholders.

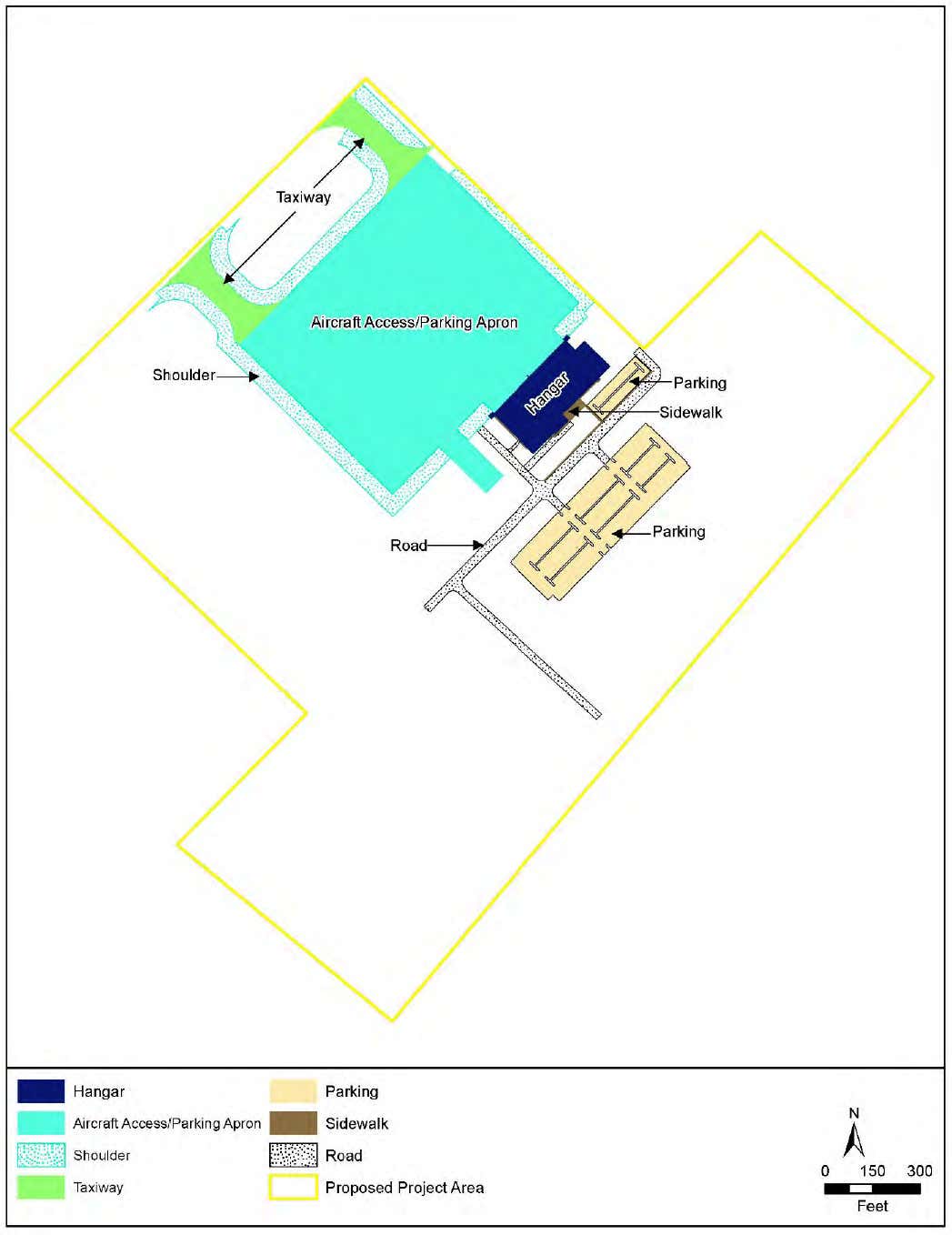

"The Navy proposes to establish facilities and functions at Naval Base Ventura County (NBVC) Point Mugu, California to support West Coast home basing and operations of the MQ-25A Stingray Carrier-based Unmanned Air System (Stingray CBUAS)," the report says. "Under the Proposed Action, the Navy would home base 20 Stingray CBUAS; construct a hangar, training facilities, and supporting infrastructure; perform air vehicle (AV) maintenance; provide training for air vehicle operators (AVOs) and maintainers; conduct approximately 960 Stingray CBUAS annual flight operations; and station approximately 730 personnel, plus their family members."

The largest single planned addition is a new hangar and associated ramp and taxiways, at the northern end of the base attached to Naval Air Station Point Mugu's Runway 03/21. NAS Point Mugu is part of the larger Naval Base Ventura County.

The new information comes from a draft environmental impact assessment regarding the construction of new facilities at Naval Base Ventura County, in Point Mugu, California, which the Navy posted online recently. These kinds of assessments are a routine part of the process of approving major new additions to U.S. military bases, which also includes input from various other federal, state, and local stakeholders.

"The Navy proposes to establish facilities and functions at Naval Base Ventura County (NBVC) Point Mugu, California to support West Coast home basing and operations of the MQ-25A Stingray Carrier-based Unmanned Air System (Stingray CBUAS)," the report says. "Under the Proposed Action, the Navy would home base 20 Stingray CBUAS; construct a hangar, training facilities, and supporting infrastructure; perform air vehicle (AV) maintenance; provide training for air vehicle operators (AVOs) and maintainers; conduct approximately 960 Stingray CBUAS annual flight operations; and station approximately 730 personnel, plus their family members."

The largest single planned addition is a new hangar and associated ramp and taxiways, at the northern end of the base attached to Naval Air Station Point Mugu's Runway 03/21. NAS Point Mugu is part of the larger Naval Base Ventura County.

In addition, there are plans for a new multi-story training facility for MQ-25 squadron personnel and a simulator facility to train operators for the drones. Point Mugu will also require the expansion of a battery shop on base to accommodate "lithium-ion battery maintenance and storage," as part of the proposed basing plan.

An existing hangar, Hangar 365, is set to receive minor renovations to support VUQ-10 and its initial cadre of drones, as well as provide space for some maintenance tasks. The Navy is hoping to begin construction of the new and expanded facilities in 2023 and have that work completed by 2025.

An existing hangar, Hangar 365, is set to receive minor renovations to support VUQ-10 and its initial cadre of drones, as well as provide space for some maintenance tasks. The Navy is hoping to begin construction of the new and expanded facilities in 2023 and have that work completed by 2025.

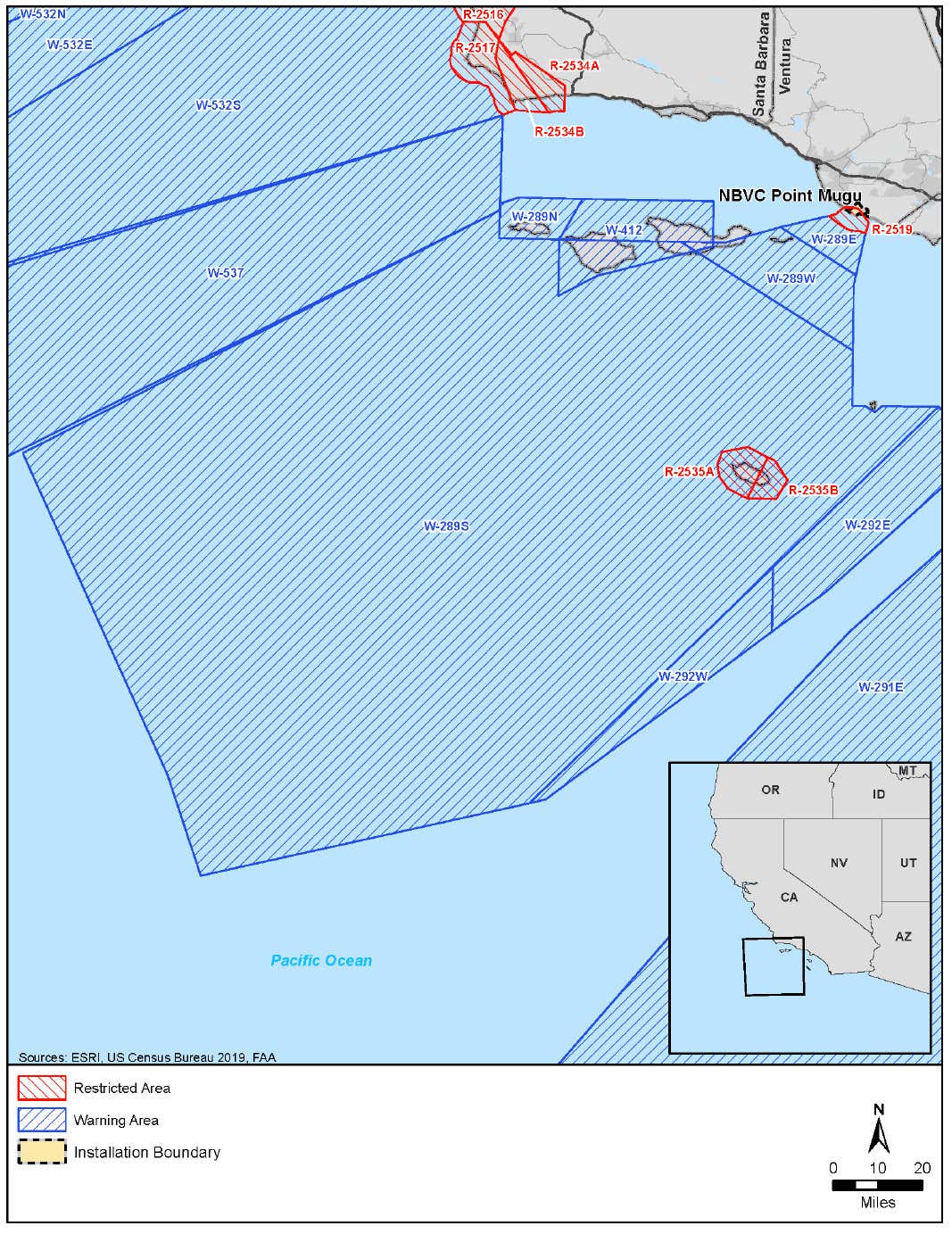

Beyond the construction plans, the report also outlines a number of important points regarding the Navy's plans for its future MQ-25 force. The squadron at Point Mugu, which will be in addition to VUQ-10, is set to be the first of at least three operational Stingray units, one more being based at a yet-to-determined location on the East Coast of the United States and another forward-deployed in Japan.

From these locations, the drones will be situated to best support U.S. carrier strike group operations originating from the East and West Coasts of the United States, as well as Japan, where the Navy maintains a forward-deployed aircraft carrier. This will also help position the MQ-25s to best support carrier strike group training, including pre-deployment Composite Training Unit Exercises (COMPTUEX), as well as other exercises. Point Mugu is particularly well-positioned near an expansive collection of training ranges off the coast of southern California that the service regularly uses for various drills, carrier-related and otherwise.

From these locations, the drones will be situated to best support U.S. carrier strike group operations originating from the East and West Coasts of the United States, as well as Japan, where the Navy maintains a forward-deployed aircraft carrier. This will also help position the MQ-25s to best support carrier strike group training, including pre-deployment Composite Training Unit Exercises (COMPTUEX), as well as other exercises. Point Mugu is particularly well-positioned near an expansive collection of training ranges off the coast of southern California that the service regularly uses for various drills, carrier-related and otherwise.

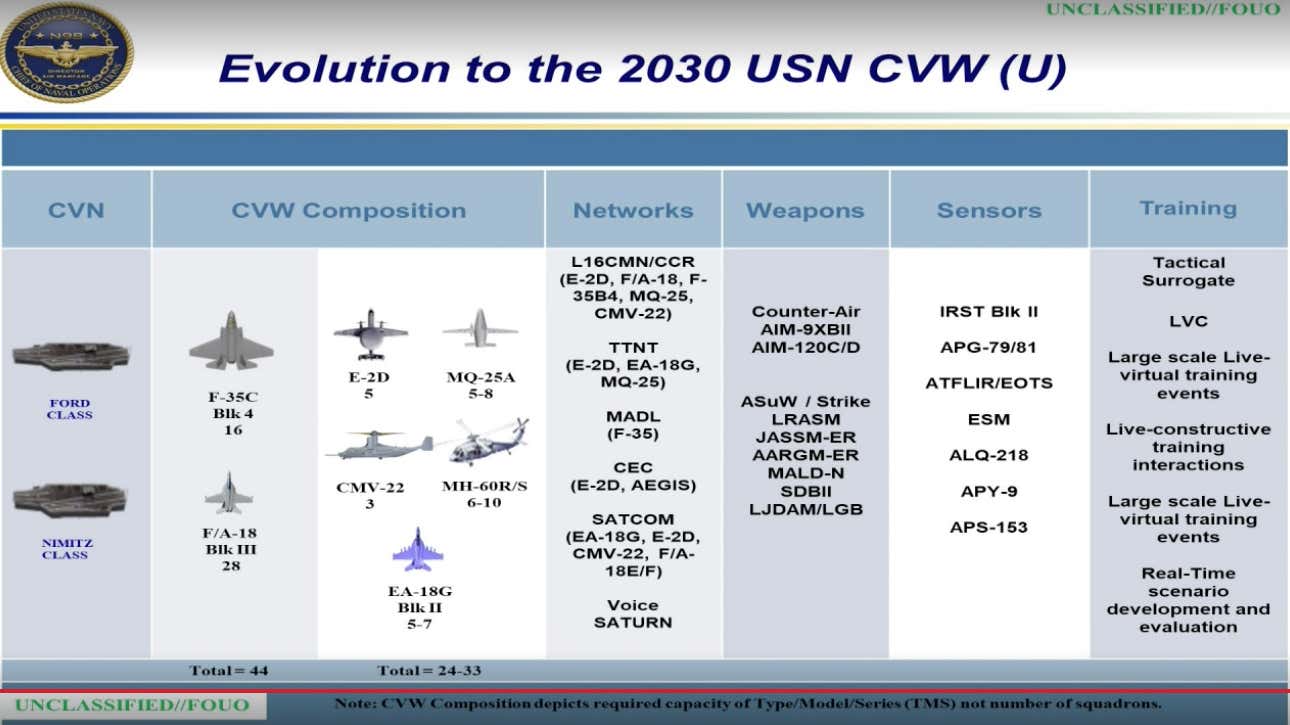

From the environmental assessment report, we also now know that the Navy plans for a typical MQ-25 squadron to have four detachments. The Navy has yet to specify exactly how many Stingrays a typical detachment will have. A briefing officials from the service presented at the Tail Association's annual symposium earlier this year, which was held online due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, said that, by 2030, a typical carrier air wing could have between five and eight of the drones.

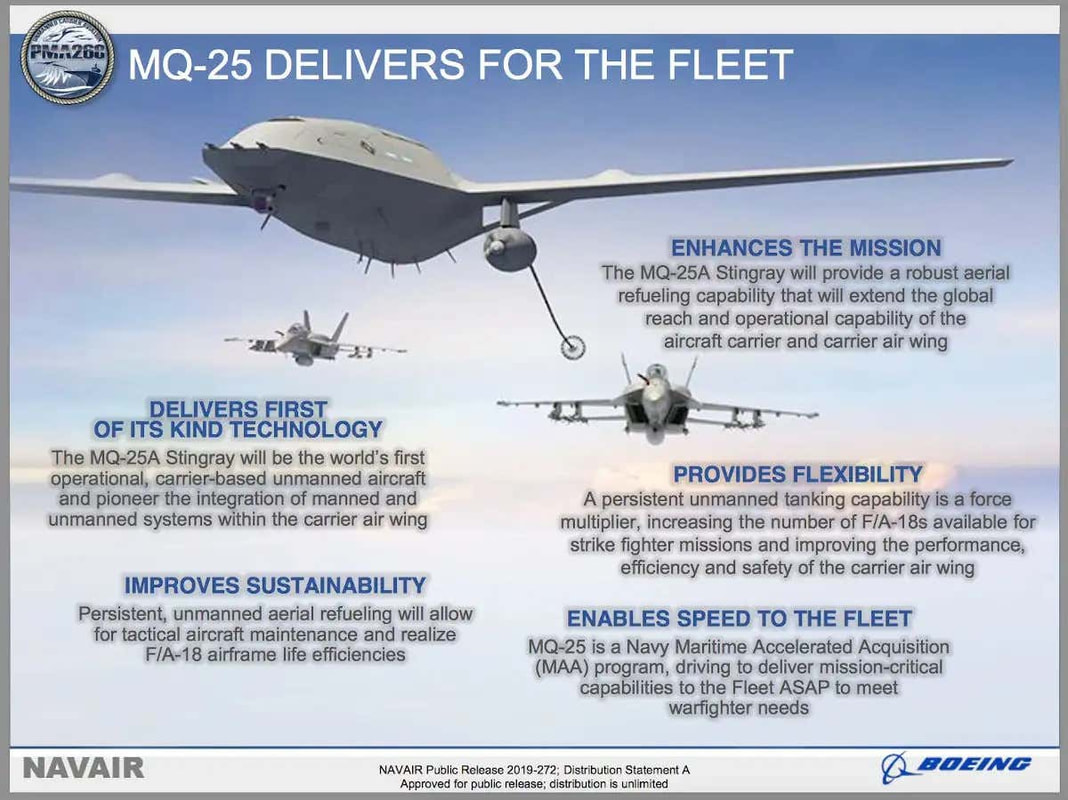

Regardless, these detachments will provide aerial refueling support to carrier air wings, a mission presently performed by F/A-18E/F Super Hornets equipped with buddy refueling stores. The tanker drones will allow those jets to focus on other missions, as well as reduce the overall strain on those aircraft, while, at the same time, significantly extending their reach. They will also be able to refuel Navy F-35C Joint Strike Fighters as they begin to deploy as part of the service's carrier air wings. In addition, the Stingrays will have a secondary intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capability from the start and could very well gain the ability to conduct other missions as time goes on.

For actual deployments, a single detachment will be attached to the assigned carrier airborne early warning squadron within the carrier air wing, units that presently fly the E-2C/D Hawkeye airborne command and control aircraft.

"At sea, detachments from the Stingray CBUAS squadron will leverage personnel and maintenance administration as well as chain of command representation of the VAW [carrier airborne early warning] squadron with the CVW [carrier air wing]," the environmental assessment report notes. "Co-locating Stingray CBUAS squadrons with VAW squadrons ashore is important due to the synergies and efficiencies of the two codependent communities."

It has already been established that the Navy's Airborne Command & Control Logistics Wing (ACCLOGWING), which presently oversees the service's E-2 Hawkeye and C-2 Greyhound fleets, the latter of which is headed for retirement in the coming years, will also be in charge of the Stingrays. The service had already revealed that the Hawkeye and Stingray communities would be particularly heavily tied together going forward, including the cross-training of E-2 crews as MQ-25 operators.

Last month, Navy personnel from Air Test and Evaluation Squadron One (VX-1) and Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 23 (VX-23) traveled to Boeing's facilities in St. Louis Missouri to do three days of simulated training relating to operating the MQ-25. VX-1 and VX-23, which are both based at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland, are responsible for testing and evaluating of various aircraft and helicopters, including unmanned platforms.

Among the naval aviators that made the trip was Lieutenant Venus Savage, the MQ-25 assistant operational test director for VX-1 and an MQ-25 air vehicle operator (AVO), who was spotted at Boeing's St. Louis' offices wearing a Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 125 (VAW-125) patch, further underscoring the burgeoning relationship between those two communities.

"Especially for operational test, we’re lucky to be involved this early in the program," Savage said in a statement. "It helps when you get that side information from an experienced AVO that adds to what’s in the documentation. We were able to ask detailed questions and get clarification on what the checklists and commands are and they let us know what to expect from the air vehicle. It helps ingrain it in your memory because it’s more than just book learning."

Pictures of the training that Navy released also notably showed a desktop computer-based control interface that is indicative of the planned semi-autonomous concept of operations for the MQ-25. Of course, it's not exactly clear how representative these simulators will be of the final ground control station design.

Boeing has also been conducting flight testing of an MQ-25 demonstrator drone, also known as T1, since September 2019. So far, it has flown 30 hours, in total. It is presently undergoing additional ground testing following the integration of an underwing buddy refueling store earlier this year.

The company is also under contract to build four Engineering Development Model (EDM) prototypes, with the goal of delivering the first one to the Navy next year. The service's present plans call for the acquisition of a fleet of at least 72 MQ-25As.

Thanks to this recent environmental assessment, we now have a much better understanding of how the Navy plans to organize and employ its future Stingrays, which are set to dramatically alter how its carrier air wings operate in the future.

"At sea, detachments from the Stingray CBUAS squadron will leverage personnel and maintenance administration as well as chain of command representation of the VAW [carrier airborne early warning] squadron with the CVW [carrier air wing]," the environmental assessment report notes. "Co-locating Stingray CBUAS squadrons with VAW squadrons ashore is important due to the synergies and efficiencies of the two codependent communities."

It has already been established that the Navy's Airborne Command & Control Logistics Wing (ACCLOGWING), which presently oversees the service's E-2 Hawkeye and C-2 Greyhound fleets, the latter of which is headed for retirement in the coming years, will also be in charge of the Stingrays. The service had already revealed that the Hawkeye and Stingray communities would be particularly heavily tied together going forward, including the cross-training of E-2 crews as MQ-25 operators.

Last month, Navy personnel from Air Test and Evaluation Squadron One (VX-1) and Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 23 (VX-23) traveled to Boeing's facilities in St. Louis Missouri to do three days of simulated training relating to operating the MQ-25. VX-1 and VX-23, which are both based at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland, are responsible for testing and evaluating of various aircraft and helicopters, including unmanned platforms.

Among the naval aviators that made the trip was Lieutenant Venus Savage, the MQ-25 assistant operational test director for VX-1 and an MQ-25 air vehicle operator (AVO), who was spotted at Boeing's St. Louis' offices wearing a Carrier Airborne Early Warning Squadron 125 (VAW-125) patch, further underscoring the burgeoning relationship between those two communities.

"Especially for operational test, we’re lucky to be involved this early in the program," Savage said in a statement. "It helps when you get that side information from an experienced AVO that adds to what’s in the documentation. We were able to ask detailed questions and get clarification on what the checklists and commands are and they let us know what to expect from the air vehicle. It helps ingrain it in your memory because it’s more than just book learning."

Pictures of the training that Navy released also notably showed a desktop computer-based control interface that is indicative of the planned semi-autonomous concept of operations for the MQ-25. Of course, it's not exactly clear how representative these simulators will be of the final ground control station design.

Boeing has also been conducting flight testing of an MQ-25 demonstrator drone, also known as T1, since September 2019. So far, it has flown 30 hours, in total. It is presently undergoing additional ground testing following the integration of an underwing buddy refueling store earlier this year.

The company is also under contract to build four Engineering Development Model (EDM) prototypes, with the goal of delivering the first one to the Navy next year. The service's present plans call for the acquisition of a fleet of at least 72 MQ-25As.

Thanks to this recent environmental assessment, we now have a much better understanding of how the Navy plans to organize and employ its future Stingrays, which are set to dramatically alter how its carrier air wings operate in the future.

Developing The MQ-25’s Ground Control Station Means Thinking Like A Mission Commander - Not A Pilot

Eric Tegler Contributor

While discussing the MQ-25, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Venus Savage offers a casually overlooked truth about the new unmanned aerial refueling tanker that the service is developing in conjunction with Boeing to refuel its Super Hornets, F-35s and E-2 Hawkeyes.

“Because the AVO [air vehicle operator] doesn’t fly the [MQ-25] in the direct sense a pilot flies a manned aircraft, disorientation is less of a concern than information overload.”

Lt. Savage is assistant operational test director for the MQ-25 with VX-1, the Navy’s operational test squadron. She’s part of a team who are co-developing the ground control station (GCS) that AVOs on aircraft carriers and at shore sites will use to direct MQ-25s to takeoff, land, and refuel tactical aircraft.

While disorientation may be a minor concern for future MQ-25 AVOs, it’s probably a familiar feeling for the Navy test team working on the GCS interface. That team is comprised of pilots and naval flight officers like Savage. The folks who eventually operate the tanker won’t be either of these things.

Instead, they’ll be a new breed of non-pilot, specialist warrant officers with their own career track. In December, the Navy announced it will train approximately 450 warrant officers in the new AVO role over the next six to 10 years.

With MQ-25 Stingrays expected to join the fleet in 2024, there’s a relatively short window to perfect not only the aircraft itself but the way AVOs will interact with it. How they’ll see the operational “picture” of the aircraft they guide won’t be remotely like the pilot of a manned airplane or even those who control conventional remotely-piloted aircraft like the Air Force’s MQ-9 Reaper.

“The display differs from a manned cockpit in that there is no image displayed of the world outside of the AV,” Lt. Savage says. “There are readouts of many of the air vehicle [AV] systems for the AVO’s reference, including a map and a primary flight display, but because the AVO is never intended to directly input singular controls to the AV, combined with the expected signal delay, this is omitted, making it distinct from a manned aircraft’s displays or view.”

Traditional aerial refueling requires precise maneuvering between two aircraft with a clear visual element for the tanker as well as the receiver. But Stingray AVOs will simply oversee join-up, contact, and refueling - not control it.

According to Lt. Savage, AVOs will input large scale commands such as a flight path or holding pattern, an altitude or direction change while running concurrent systems like the Stingray’s fuel pod or landing gear. “The logic within the aircraft will resolve [these] requests as compatible with its current phase of flight,” she says.

Operational management without a cockpit sight picture will be more akin to what mission and air controllers aboard E-2 Hawkeye early-warning/control aircraft do. That may explain why the Navy will reportedly attach MQ-25 units to E-2 squadrons including Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10 (VUQ-10), the first Stingray squadron.

But choosing what info to present to an “operator” is different than choosing what to present to a pilot and those decisions are still in flux. The prototype GCS display consists primarily of dropdown menus, input windows and guarded digital buttons and switches Savage says.

“Part of the continued system refinement is making sure that the AVO displays are concise while remaining effective, so the AVO does not have to wade through unnecessary menus or pop-ups.”

The “TMI” problem could be compounded by the fact that AVOs will have none of the sensory input that pilots of manned aircraft have, “seat of the pants” or otherwise. Without such crucial, real-time input, AVOs will have to rely on select alerts or audiovisual cues on their GCS screens.

VX-1 personnel including Lt. Savage went to Boeing’s St. Louis facility last October to gain more experience with the MQ-25 AVO GCS simulator and to observe Boeing AVOs put T-1, the pre-MQ-25 test aircraft, through its paces in real flight.

“They are still working to present and integrate all the controls that will be needed for an AVO to successfully command a mission with the MQ-25,” Savage reports. “Some of the warnings, menus, interfaces and other parts of the software are continually being tweaked, and we expect the final version will look different than this simulator.”

While the Stingray is expected to seamlessly slot into operations on a carrier deck and in the air, its autonomous decision-making and loose AVO guidance mean that the aircraft will need a new set of rules for safe operation known as NATOPS (Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization).

But MQ-25 NATOPS will likely have to wait until there’s an actual MQ-25 EDM (Engineering Development Model) delivered later this year.

At Boeing, Lt. Savage sat in as the “AVO3” - an observer and flight test backup to the pilot in command during a T1 test flight. She has no previous experience in a tanker or receiver aircraft and “minimal” experience with other remote-pilot vehicle stations. Other team members have Super Hornet tanker and receiver experience and E-2 backgrounds.

However a lack of such experience may not be a handicap since the test team sought a diversity of experience which “avoids biasing development towards similarity to current aircraft cockpits,” Savage explains.

While the Navy and Boeing may want a GCS interface that avoids similarity to an aircraft cockpit, they may not mind one that bears resemblance to a shipboard fighter controller (air traffic control) station or an E-2 Hawkeye Combat Information Center Officer’s (CICO) station.

That would be familiar territory for Lt. Savage who served as a Hawkeye back-seater with VAW-125. Refueling operations aren’t as familiar, likely less so with the Stingray.

“The commands are different from a manned tanker because [MQ-25 AVOs] rely on a lot more automatic safety features and behaviors than a manned platform requires. The Navy and Boeing are working closely together to sort out the best methods to close those communication gaps that are inherently created by this type of system.”

It’s only the start of their work. Perfecting operational unmanned aerial refueling will take years, not to mention perfecting the Stingray’s potential combat capabilities.

“Because the AVO [air vehicle operator] doesn’t fly the [MQ-25] in the direct sense a pilot flies a manned aircraft, disorientation is less of a concern than information overload.”

Lt. Savage is assistant operational test director for the MQ-25 with VX-1, the Navy’s operational test squadron. She’s part of a team who are co-developing the ground control station (GCS) that AVOs on aircraft carriers and at shore sites will use to direct MQ-25s to takeoff, land, and refuel tactical aircraft.

While disorientation may be a minor concern for future MQ-25 AVOs, it’s probably a familiar feeling for the Navy test team working on the GCS interface. That team is comprised of pilots and naval flight officers like Savage. The folks who eventually operate the tanker won’t be either of these things.

Instead, they’ll be a new breed of non-pilot, specialist warrant officers with their own career track. In December, the Navy announced it will train approximately 450 warrant officers in the new AVO role over the next six to 10 years.

With MQ-25 Stingrays expected to join the fleet in 2024, there’s a relatively short window to perfect not only the aircraft itself but the way AVOs will interact with it. How they’ll see the operational “picture” of the aircraft they guide won’t be remotely like the pilot of a manned airplane or even those who control conventional remotely-piloted aircraft like the Air Force’s MQ-9 Reaper.

“The display differs from a manned cockpit in that there is no image displayed of the world outside of the AV,” Lt. Savage says. “There are readouts of many of the air vehicle [AV] systems for the AVO’s reference, including a map and a primary flight display, but because the AVO is never intended to directly input singular controls to the AV, combined with the expected signal delay, this is omitted, making it distinct from a manned aircraft’s displays or view.”

Traditional aerial refueling requires precise maneuvering between two aircraft with a clear visual element for the tanker as well as the receiver. But Stingray AVOs will simply oversee join-up, contact, and refueling - not control it.

According to Lt. Savage, AVOs will input large scale commands such as a flight path or holding pattern, an altitude or direction change while running concurrent systems like the Stingray’s fuel pod or landing gear. “The logic within the aircraft will resolve [these] requests as compatible with its current phase of flight,” she says.

Operational management without a cockpit sight picture will be more akin to what mission and air controllers aboard E-2 Hawkeye early-warning/control aircraft do. That may explain why the Navy will reportedly attach MQ-25 units to E-2 squadrons including Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10 (VUQ-10), the first Stingray squadron.

But choosing what info to present to an “operator” is different than choosing what to present to a pilot and those decisions are still in flux. The prototype GCS display consists primarily of dropdown menus, input windows and guarded digital buttons and switches Savage says.

“Part of the continued system refinement is making sure that the AVO displays are concise while remaining effective, so the AVO does not have to wade through unnecessary menus or pop-ups.”

The “TMI” problem could be compounded by the fact that AVOs will have none of the sensory input that pilots of manned aircraft have, “seat of the pants” or otherwise. Without such crucial, real-time input, AVOs will have to rely on select alerts or audiovisual cues on their GCS screens.

VX-1 personnel including Lt. Savage went to Boeing’s St. Louis facility last October to gain more experience with the MQ-25 AVO GCS simulator and to observe Boeing AVOs put T-1, the pre-MQ-25 test aircraft, through its paces in real flight.

“They are still working to present and integrate all the controls that will be needed for an AVO to successfully command a mission with the MQ-25,” Savage reports. “Some of the warnings, menus, interfaces and other parts of the software are continually being tweaked, and we expect the final version will look different than this simulator.”

While the Stingray is expected to seamlessly slot into operations on a carrier deck and in the air, its autonomous decision-making and loose AVO guidance mean that the aircraft will need a new set of rules for safe operation known as NATOPS (Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization).

But MQ-25 NATOPS will likely have to wait until there’s an actual MQ-25 EDM (Engineering Development Model) delivered later this year.

At Boeing, Lt. Savage sat in as the “AVO3” - an observer and flight test backup to the pilot in command during a T1 test flight. She has no previous experience in a tanker or receiver aircraft and “minimal” experience with other remote-pilot vehicle stations. Other team members have Super Hornet tanker and receiver experience and E-2 backgrounds.

However a lack of such experience may not be a handicap since the test team sought a diversity of experience which “avoids biasing development towards similarity to current aircraft cockpits,” Savage explains.

While the Navy and Boeing may want a GCS interface that avoids similarity to an aircraft cockpit, they may not mind one that bears resemblance to a shipboard fighter controller (air traffic control) station or an E-2 Hawkeye Combat Information Center Officer’s (CICO) station.

That would be familiar territory for Lt. Savage who served as a Hawkeye back-seater with VAW-125. Refueling operations aren’t as familiar, likely less so with the Stingray.

“The commands are different from a manned tanker because [MQ-25 AVOs] rely on a lot more automatic safety features and behaviors than a manned platform requires. The Navy and Boeing are working closely together to sort out the best methods to close those communication gaps that are inherently created by this type of system.”

It’s only the start of their work. Perfecting operational unmanned aerial refueling will take years, not to mention perfecting the Stingray’s potential combat capabilities.

This drone will refuel Naval fighter jets by 2024

The MQ-25A Stingray will take off and land from aircraft carriers and is critical to the Navy's future vision.

BY KELSEY D. ATHERTON MARCH 25, 2021

When the Navy’s Super Hornet fighter jets take off from an aircraft carrier, they are sometimes accompanied by squadmates loaded down with five extra tanks of fuel. A few hundred miles into the mission, these fighter-jet tankers will top off the tanks of their compatriots, boosting their range, before heading back. This is complex, difficult work, and it strains their air frames. But by 2024, the Navy plans to have that work done instead by a sophisticated, autonomous drone called the MQ-25A Stingray, which will operate from carriers as a tanker and let the fighters do the fighting.

On a runway, the MQ-25A Stingray looks like half a plane. Its sleek, gray body, with narrow wings and condensed fuselage, gives it an appearance that is somewhere between a fictional starfighter and a real-world stunt jet with the cockpit lobbed off. Built by Boeing, the Stingray is a wholly uninhabited airframe, made to autonomously refuel other fighters mid-air. It’s crucial to the US Navy’s vision of war robots for the future, and it will soon be flying routine missions near California’s channel islands.

On March 16th, the Navy released its Unmanned Campaign Framework, outlining the present state of Navy robotics and how it intends to evolve those capabilities for the future. That same week, the Navy released its environmental impact assessment for basing the Stingray at Naval Base Ventura County in California. The future of the Navy is one filled with robots, and the Stingray will be crucial to seeing that vision realized.

The Navy expects the Stingray to enter service as part of normal operations in 2024, though the service has been less forthcoming on earlier milestones. When it does so, it will be the culmination of an 18-year long journey, an ambitious accomplishment nonetheless scaled down from the grand visions put forth for super capable flying robots in the mid-2000s.

The story of the Stingray is the story not just of the MQ-25A, but of the expansive vision for combat drones that preceded it, and of the future of robot fighters that will likely build on its success.

“The Stingray is emblematic of this push to grow the envelope of what uninhabited vehicles can do and their roles on the battlefield,” says Dan Gettinger, an analyst at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies and an independent consultant. “We’ve had drones proposed for resupplying infantry [and] for carrying cargo—that isn’t new—but taking us to an air-to-air tanker mission is pretty novel in the history of drones.”

In the present, the Stingray has to prove that it can do three difficult tasks well, and do them repeatedly. Every aircraft carrier is a small runway, and launching from that short runway is often aided by a catapult, which hurls the plane into the sky with extra momentum. Landing on a carrier is harder, as the runway isn’t just small—it is also moving on water.

Human pilots train for this in simulators and then repeatedly while underway, mastering day landings and then moving on to night approaches. The Stingray will have to do it all autonomously, with algorithms and sensors supplanting human experience and knowledge.

In the air, the Stingray’s primary mission will be the aforementioned aerial refueling. This involves flying out 500 miles, dangling an ovipositor-like tube into a special refueling spigot on the receiving plane, maintaining steady flight until the fighter’s tank is topped off, and then repeating the process until the tanker has exhausted the 15,000 pounds of fuel it carries for this purpose. (Sometimes, it will also involve flying out to meet fighters as they return from a mission, and topping off the tank so they have enough juice to get home.)

When human pilots are in both airborne vehicles as they are now, they can, if all else fails, at least radio each other to communicate and make sure everything lines up. Flying autonomously, the Stingray will have to rely instead on its programming, and on the limited means of responding to humans in-flight to handle any of this bumpiness

“The MQ-25 will give us the ability to extend the air wing out probably 300 or 400 miles beyond where we typically go,” Vice Admiral MikeShoemaker told the US Naval Institute magazine Proceedings in September 2017. “We will be able to do that and sustain a nominal number of airplanes at that distance.”

A Super Hornet can fly about 450 miles before needing to return for refueling. While the current strategy of using Hornets to refuel other Hornets is effective, every refueling demands human pilots, and keeps useful fighters from participating in long-range attacks. It also increases the wear and tearon the Super Hornets that fly as carriers, shortening the overall lifetime expectancy of the fleet. Handing that mission off to a drone frees up existing Super Hornets and human pilots for the far-reaching missions.

What the Stringray does is the fundamentally unflashy support work of war. Having them in the fleet makes the fighters better, and it means that the carriers the fighters fly from are able to stay further away from danger, or able to send fighters further afield to harder-to-hit foes. The Stingray facilitates air war, even if its main mode of operations will be as a fuel depot in the sky between the runway and where the bombs hit.

It is a modest start for a program that can trace its roots back to the early 21st century. In 2006 the Navy was exploring what, exactly, it could do with flying robots. A defense budget from October 2000 had called for “one-third of the aircraft in the operational deep strike force aircraft fleet” to be uninhabited by 2010. For the Navy, this meant developing a stealthy, autonomous, carrier-based Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle-Navy.

A report from the Congressional Research Service in October 2006 outlined this vision. UCAV-N’s first mission would be surveillance, and its second would be the suppression of enemy air defenses and strike operations. (Suppression can be done with jammers or electronic warfare, messing up sensors; the second part refers to the use of bombs, missiles, and bullets.)

Development on a combat drone for the Navy started with DARPA in 2003, with research then handed off to a joint Air Force and Navy office in 2005, before the program became entirely Naval in 2006. This program paid off in the X-47B, a wedge-shaped autonomous drone that first flew in 2011.

Built as an experimental technology demonstrator, the X-47B was capable of taking off from and landing on an aircraft carrier, though it didn’t always stick the landing. In later flights, it demonstrated the ability to fly with fighters in formation, and as a finale of sorts, it was even successfully refueled in mid-air.

[Related: China is building drone planes for its aircraft carriers]

After the X-47B, it was expected that the Navy would look to develop the drone out into a fully fledged combat aircraft, capable of following human-issued orders to find enemies and drop bombs on them. Instead, the Navy scaled back the scopes of its vision for uninhabited aircraft, moving it away from direct combat.

In part driven by a slight budgetary constraint, the Navy looked to move its drone out of a combat role and into intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance instead. This work was what grew the Air Force’s drone program, with Predators starting as unarmed scouts before adding weapons, and leading to the Reaper line of scouts armed from the beginning.

“[The] idea from the start was that the Stingray could perhaps in the future take on the missions that were envisioned for the X-47B, but until last week there wasn’t much word from the Navy on expanding that mission set beyond the tanker role,” Gettinger says.

As Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus outlined in 2014, “the end state is an autonomous aircraft capable of precision strike in a contested environment, and it is expected to grow and expand its missions so that it is capable of extended range intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, electronic warfare, tanking, and maritime domain awareness.”

That may still remain the end state in mind, but the Stingray is going to get there first by figuring out how to be a reliable tanker, and then by adding scouting onto an already successful tanker platform. The Navy set out to make its big carrier drone a tanker in 2016, over the objections of Congress, which wanted to focus that energy instead on an attack aircraft.

That switch to a tanker also meant that Northrop Grumman, which built the X-47B, decided to exit the competition for the contract, which was ultimately won by Boeing.

At a Capitol Hill hearing about the Navy’s new Unmanned Campaign Framework, Vice Admiral James Kilby floated the possibility that the Stingray’s capable airframe could take on tasks and payloads beyond that of mid-air refueling.

“Let’s move to [intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance], maybe electronic attack, strike, and then other things as complexity grows across that mission set,” Kilby said. “But I think the MQ-25 has great promise for us.”

Electronic warfare, broadly, refers to jammers and other weapons that interfere with or incapacitate electronic systems, through means other than explosive destruction. The Stingray could be another way for carriers to put weapons on far-away targets, be they tanks, radar installations, or people marked as enemies.

Getting the Stingray, or some other drone built on its success, to fly those missions will be crucial if the Navy is to reach “upwards of 40 percent of the aircraft in an air wing that are unmanned,” as Kilby promised in that same hearing.

Before all of this happens, the Stingray fleet will need to settle into its new home, the naval base at Point Mugu, just west of Malibu in Ventura County on the Pacific coast.

On a runway, the MQ-25A Stingray looks like half a plane. Its sleek, gray body, with narrow wings and condensed fuselage, gives it an appearance that is somewhere between a fictional starfighter and a real-world stunt jet with the cockpit lobbed off. Built by Boeing, the Stingray is a wholly uninhabited airframe, made to autonomously refuel other fighters mid-air. It’s crucial to the US Navy’s vision of war robots for the future, and it will soon be flying routine missions near California’s channel islands.

On March 16th, the Navy released its Unmanned Campaign Framework, outlining the present state of Navy robotics and how it intends to evolve those capabilities for the future. That same week, the Navy released its environmental impact assessment for basing the Stingray at Naval Base Ventura County in California. The future of the Navy is one filled with robots, and the Stingray will be crucial to seeing that vision realized.

The Navy expects the Stingray to enter service as part of normal operations in 2024, though the service has been less forthcoming on earlier milestones. When it does so, it will be the culmination of an 18-year long journey, an ambitious accomplishment nonetheless scaled down from the grand visions put forth for super capable flying robots in the mid-2000s.

The story of the Stingray is the story not just of the MQ-25A, but of the expansive vision for combat drones that preceded it, and of the future of robot fighters that will likely build on its success.

“The Stingray is emblematic of this push to grow the envelope of what uninhabited vehicles can do and their roles on the battlefield,” says Dan Gettinger, an analyst at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies and an independent consultant. “We’ve had drones proposed for resupplying infantry [and] for carrying cargo—that isn’t new—but taking us to an air-to-air tanker mission is pretty novel in the history of drones.”

In the present, the Stingray has to prove that it can do three difficult tasks well, and do them repeatedly. Every aircraft carrier is a small runway, and launching from that short runway is often aided by a catapult, which hurls the plane into the sky with extra momentum. Landing on a carrier is harder, as the runway isn’t just small—it is also moving on water.

Human pilots train for this in simulators and then repeatedly while underway, mastering day landings and then moving on to night approaches. The Stingray will have to do it all autonomously, with algorithms and sensors supplanting human experience and knowledge.

In the air, the Stingray’s primary mission will be the aforementioned aerial refueling. This involves flying out 500 miles, dangling an ovipositor-like tube into a special refueling spigot on the receiving plane, maintaining steady flight until the fighter’s tank is topped off, and then repeating the process until the tanker has exhausted the 15,000 pounds of fuel it carries for this purpose. (Sometimes, it will also involve flying out to meet fighters as they return from a mission, and topping off the tank so they have enough juice to get home.)

When human pilots are in both airborne vehicles as they are now, they can, if all else fails, at least radio each other to communicate and make sure everything lines up. Flying autonomously, the Stingray will have to rely instead on its programming, and on the limited means of responding to humans in-flight to handle any of this bumpiness

“The MQ-25 will give us the ability to extend the air wing out probably 300 or 400 miles beyond where we typically go,” Vice Admiral MikeShoemaker told the US Naval Institute magazine Proceedings in September 2017. “We will be able to do that and sustain a nominal number of airplanes at that distance.”

A Super Hornet can fly about 450 miles before needing to return for refueling. While the current strategy of using Hornets to refuel other Hornets is effective, every refueling demands human pilots, and keeps useful fighters from participating in long-range attacks. It also increases the wear and tearon the Super Hornets that fly as carriers, shortening the overall lifetime expectancy of the fleet. Handing that mission off to a drone frees up existing Super Hornets and human pilots for the far-reaching missions.

What the Stringray does is the fundamentally unflashy support work of war. Having them in the fleet makes the fighters better, and it means that the carriers the fighters fly from are able to stay further away from danger, or able to send fighters further afield to harder-to-hit foes. The Stingray facilitates air war, even if its main mode of operations will be as a fuel depot in the sky between the runway and where the bombs hit.

It is a modest start for a program that can trace its roots back to the early 21st century. In 2006 the Navy was exploring what, exactly, it could do with flying robots. A defense budget from October 2000 had called for “one-third of the aircraft in the operational deep strike force aircraft fleet” to be uninhabited by 2010. For the Navy, this meant developing a stealthy, autonomous, carrier-based Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle-Navy.

A report from the Congressional Research Service in October 2006 outlined this vision. UCAV-N’s first mission would be surveillance, and its second would be the suppression of enemy air defenses and strike operations. (Suppression can be done with jammers or electronic warfare, messing up sensors; the second part refers to the use of bombs, missiles, and bullets.)

Development on a combat drone for the Navy started with DARPA in 2003, with research then handed off to a joint Air Force and Navy office in 2005, before the program became entirely Naval in 2006. This program paid off in the X-47B, a wedge-shaped autonomous drone that first flew in 2011.

Built as an experimental technology demonstrator, the X-47B was capable of taking off from and landing on an aircraft carrier, though it didn’t always stick the landing. In later flights, it demonstrated the ability to fly with fighters in formation, and as a finale of sorts, it was even successfully refueled in mid-air.

[Related: China is building drone planes for its aircraft carriers]

After the X-47B, it was expected that the Navy would look to develop the drone out into a fully fledged combat aircraft, capable of following human-issued orders to find enemies and drop bombs on them. Instead, the Navy scaled back the scopes of its vision for uninhabited aircraft, moving it away from direct combat.

In part driven by a slight budgetary constraint, the Navy looked to move its drone out of a combat role and into intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance instead. This work was what grew the Air Force’s drone program, with Predators starting as unarmed scouts before adding weapons, and leading to the Reaper line of scouts armed from the beginning.

“[The] idea from the start was that the Stingray could perhaps in the future take on the missions that were envisioned for the X-47B, but until last week there wasn’t much word from the Navy on expanding that mission set beyond the tanker role,” Gettinger says.

As Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus outlined in 2014, “the end state is an autonomous aircraft capable of precision strike in a contested environment, and it is expected to grow and expand its missions so that it is capable of extended range intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, electronic warfare, tanking, and maritime domain awareness.”

That may still remain the end state in mind, but the Stingray is going to get there first by figuring out how to be a reliable tanker, and then by adding scouting onto an already successful tanker platform. The Navy set out to make its big carrier drone a tanker in 2016, over the objections of Congress, which wanted to focus that energy instead on an attack aircraft.

That switch to a tanker also meant that Northrop Grumman, which built the X-47B, decided to exit the competition for the contract, which was ultimately won by Boeing.

At a Capitol Hill hearing about the Navy’s new Unmanned Campaign Framework, Vice Admiral James Kilby floated the possibility that the Stingray’s capable airframe could take on tasks and payloads beyond that of mid-air refueling.

“Let’s move to [intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance], maybe electronic attack, strike, and then other things as complexity grows across that mission set,” Kilby said. “But I think the MQ-25 has great promise for us.”

Electronic warfare, broadly, refers to jammers and other weapons that interfere with or incapacitate electronic systems, through means other than explosive destruction. The Stingray could be another way for carriers to put weapons on far-away targets, be they tanks, radar installations, or people marked as enemies.

Getting the Stingray, or some other drone built on its success, to fly those missions will be crucial if the Navy is to reach “upwards of 40 percent of the aircraft in an air wing that are unmanned,” as Kilby promised in that same hearing.

Before all of this happens, the Stingray fleet will need to settle into its new home, the naval base at Point Mugu, just west of Malibu in Ventura County on the Pacific coast.

Navy Establishes First Squadron To Operate Its Carrier-Based MQ-25 Stingray Tanker Drones

The Navy is standing up the unit to ensure personnel are as prepared as they can be for the arrival of these drones in the coming years. BY JOSEPH TREVITHICK OCTOBER 1, 2020

A year from now, the U.S. Navy will have officially established the first squadron that will operate its future MQ-25 Stingray carrier-based unmanned tankers from Boeing. The service does not expect to begin test flying more refined MQ-25 prototypes from actual carriers until the end of next year, at the earliest. As such, this unit will be focused on training personnel to be as ready as possible to operate and maintain those drones when they begin arriving in the coming years.

The Navy first began the formal processing of standing up Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10, abbreviated VUQ-10, in August, according to an official internal notice. That document says the official establishment date is Oct. 1, 2021, and that the unit will be located at Naval Base Ventura Country in California, which includes Naval Air Station Point Mugu. A detachment of Unmanned Patrol Squadron 19 (VUP-19), the Navy's first MQ-4C Triton maritime surveillance drone unit, also calls Point Mugu home.

The Navy first began the formal processing of standing up Unmanned Carrier Launched Multi-Role Squadron 10, abbreviated VUQ-10, in August, according to an official internal notice. That document says the official establishment date is Oct. 1, 2021, and that the unit will be located at Naval Base Ventura Country in California, which includes Naval Air Station Point Mugu. A detachment of Unmanned Patrol Squadron 19 (VUP-19), the Navy's first MQ-4C Triton maritime surveillance drone unit, also calls Point Mugu home.

The notice also says that VUQ-10 will be assigned to the Navy's Airborne Command & Control Logistics Wing (ACCLOGWING), which presently oversees the service's E-2 Hawkeye and C-2 Greyhound fleets. The Wing's website already says that it is involved in the Stingray drone program through the MQ-25 Fleet Integration Team (FIT).

From ACCLOGWING, the rest of VUQ-10's chain of command then goes first to Naval Air Forces Pacific and then U.S. Pacific Fleet. This appears to be purely for administrative purposes. The Navy has said in the past that the Nimitz-class carriers USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and USS George H.W. Bush, both of which are homeported in Norfolk, Virginia on the East Coast of the United States, would be the first to receive the necessary equipment to operate the MQ-25s.

From ACCLOGWING, the rest of VUQ-10's chain of command then goes first to Naval Air Forces Pacific and then U.S. Pacific Fleet. This appears to be purely for administrative purposes. The Navy has said in the past that the Nimitz-class carriers USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and USS George H.W. Bush, both of which are homeported in Norfolk, Virginia on the East Coast of the United States, would be the first to receive the necessary equipment to operate the MQ-25s.

VUQ-10's official role will be as the so-called Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS) for the MQ-25, making it responsible for training crews to operate the drones, as well as ground personnel to maintain them. Standing up the FRS now will "allow personnel time to attain advanced qualifications ahead of aircraft delivery," according to the Navy notice.

That being said, depending on the overall size of the MQ-25 fleet, initially, detachments from VUQ-10 may also have an operational role. "To conduct, through self-sustaining detachments, long-range aerial refueling support to joint force maritime component commanders, carrier strike groups, and naval task forces as directed by numbered fleet commanders," is the unit's official mission, per the official document regarding its establishment.

It seems likely that the squadron will also be heavily involved in the development of new tactics, techniques, and procedures around the operation of the drones and their place in the Navy's future carrier air wings. Being based at Point Mugu would give the unit easy access to the Navy's expansive training off the coast of Southern California, where carriers and other vessels, as well as the service's own aircraft and those from other branches of the U.S. military, regularly train.

The Navy has said that it expects to buy at least 72 Stingrays, for a total cost of around $13 billion, and that it hopes to reach initial operational capability with the type in 2024. At present, Boeing is under contract to build four Engineering Development Model (EDM) prototypes, the first of which it hopes to deliver next year. For more than a year now, the company has already been conducting various ground and flight tests using a demonstrator drone, known as T1.

The primary mission of the Stingrays will be to providing aerial refueling support to carrier air wings, a role presently filled by F/A-18E/F Super Hornets carrying buddy refueling stores. The MQ-25 will allow those manned fighter jets to focus on other missions and otherwise reducing the strain on those aircraft. The drones are also expected to significantly increase the overall reach of the carrier's fixed wing strike aircraft.

That being said, depending on the overall size of the MQ-25 fleet, initially, detachments from VUQ-10 may also have an operational role. "To conduct, through self-sustaining detachments, long-range aerial refueling support to joint force maritime component commanders, carrier strike groups, and naval task forces as directed by numbered fleet commanders," is the unit's official mission, per the official document regarding its establishment.

It seems likely that the squadron will also be heavily involved in the development of new tactics, techniques, and procedures around the operation of the drones and their place in the Navy's future carrier air wings. Being based at Point Mugu would give the unit easy access to the Navy's expansive training off the coast of Southern California, where carriers and other vessels, as well as the service's own aircraft and those from other branches of the U.S. military, regularly train.

The Navy has said that it expects to buy at least 72 Stingrays, for a total cost of around $13 billion, and that it hopes to reach initial operational capability with the type in 2024. At present, Boeing is under contract to build four Engineering Development Model (EDM) prototypes, the first of which it hopes to deliver next year. For more than a year now, the company has already been conducting various ground and flight tests using a demonstrator drone, known as T1.

The primary mission of the Stingrays will be to providing aerial refueling support to carrier air wings, a role presently filled by F/A-18E/F Super Hornets carrying buddy refueling stores. The MQ-25 will allow those manned fighter jets to focus on other missions and otherwise reducing the strain on those aircraft. The drones are also expected to significantly increase the overall reach of the carrier's fixed wing strike aircraft.

There is already discussion, however, about using these unmanned aircraft in other roles beyond tanking, including for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions. The Navy has also said that it expects drones, including designs beyond the MQ-25, to become an increasingly larger and more important part of carrier air wings in the future. VUQ-10 will play an important role in laying the groundwork for future unmanned operations from carrier decks, broadly.

The squadron, and the personnel that will be assigned to it, now looks set to blaze the trail for the MQ-25s, as well as subsequent carrier-based unmanned aircraft, which are set to fundamentally change the character of the Navy's future carrier air wings.

Correction: The original version of this story said that the effective formal establishment date for VUQ-10 was Oct. 1, 2020. The date is actually Oct. 1, 2021.

Contact the author: [email protected]

The squadron, and the personnel that will be assigned to it, now looks set to blaze the trail for the MQ-25s, as well as subsequent carrier-based unmanned aircraft, which are set to fundamentally change the character of the Navy's future carrier air wings.

Correction: The original version of this story said that the effective formal establishment date for VUQ-10 was Oct. 1, 2020. The date is actually Oct. 1, 2021.

Contact the author: [email protected]